Western Washington University Western Washington University

Western CEDAR Western CEDAR

WWU Honors Program Senior Projects WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship

Spring 2018

Politics of Reproductive Justice: Planned Parenthood Activism in Politics of Reproductive Justice: Planned Parenthood Activism in

Shades of Blue, Red, and Pink Shades of Blue, Red, and Pink

Sarah Petry

Western Washington University

Follow this and additional works at: https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors

Part of the Higher Education Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Petry, Sarah, "Politics of Reproductive Justice: Planned Parenthood Activism in Shades of Blue, Red, and

Pink" (2018).

WWU Honors Program Senior Projects

. 94.

https://cedar.wwu.edu/wwu_honors/94

This Project is brought to you for free and open access by the WWU Graduate and Undergraduate Scholarship at

Western CEDAR. It has been accepted for inclusion in WWU Honors Program Senior Projects by an authorized

administrator of Western CEDAR. For more information, please contact [email protected].

!

1

Politics of Reproductive Justice:

Planned Parenthood Activism in Shades of Blue, Red, and Pink

SARAH PETRY

Western Washington University

Sociology Senior Thesis, June 2018

In this paper I examine Planned Parenthood’s activism in two politically different states.

Drawing on political opportunity theory and intersectional feminist theory, I question if

and how Planned Parenthood is engaging with issues of intersectionality in these two

states. In addition, I question if they are focusing on issues of reproductive justice, not

only reproductive rights. After conducting semi-structured interviews (N=6), I show that

Planned Parenthood has an increasingly intersectional focus, especially in their coalition

work, and that they are engaging with reproductive justice issues by centering their

patients and considering the multiple barriers that different communities face in

accessing reproductive health care.

Planned Parenthood is a nationally significant provider of women’s health, especially

reproductive care and family planning services. One in five women will receive care at Planned

Parenthood at some point in her life

(PPFA 2018a). In particular, Planned Parenthood health

centers serve many vulnerable

1

populations: poor women, women living in rural areas, women of

color. Planned Parenthood’s patients are primarily individuals who face various oppressive

structures of race, class, sex, and gender, all of which impact their ability to access and receive

quality health care – both reproductive and otherwise.

Since the 2016 election, Planned Parenthood has constantly been fighting against anti-

choice policies pushed forward by the Republican controlled national legislature and White

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

1

The Affordable Care Act (2010) describes “vulnerable” populations as those that are racial and

ethnic minorities, homeless, incarcerated, and/or veterans.

!

2

House

2

. Legislators in Washington, D.C., are determined to strip Planned Parenthood’s federal

funding

3

and delegitimize the organization. In states across the country, other Republican

legislators are working to erode Planned Parenthood’s funding

4

, forcing the closure of health

clinics that serve populations who might otherwise have no access to health services for

hundreds of miles, and seeking to control women’s bodies, especially regarding their very

personal and vital reproductive health and choices.

Because Planned Parenthood clinics serve predominately women, who are more likely to

be poor, more likely to experience the negative health effects of lived racism and sexism, who

have historically been denied the reproductive control over their own bodies that Planned

Parenthood offers, proponents of Planned Parenthood argue that it is of vital importance that

these clinics stay open (PPFA 2017). Without Planned Parenthood clinics, women from rural

areas, for example, are less likely to be able to access health care, less likely to have access to

birth control, and more likely to have unwanted pregnancies that they must bear to term. As

such, Planned Parenthood Action Fund (PPAF), the political arm of Planned Parenthood, lobbies

the legislature, does electoral work, and advocates for their patients to ensure that those patients,

who rely on Planned Parenthood health centers for medically necessary care, can continue to

access those clinics and the services they provide (PPAF 2018). After the 2016 election, PPAF

adopted the motto “These Doors Stay Open”, promising to the public, to the people they serve, to

continue to provide health care to those who need it the most and who, without Planned

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

2

For example, the current administration is attempting to remake the Title X program, which

“provides preventive health care to those most in need”, enabling low-income women to access

birth control, STD tests, cancer screenings, and regular check ups. (PPAF 2018)

3

Planned Parenthood receives funding from the federal government, but they cannot use those

funds for abortion services, which are the services that the administration opposes.

4

For example, in Iowa, the legislature passed a bill that blocks Planned Parenthood from

receiving grant funds that help them provide accurate sex-education to Iowan youth.

!

3

Parenthood, might not have it at all (PPAF 2018). PPAF’s actions, because of their political

nature, deeply affect women’s access to care and, often, their lives more generally

5

.

Planned Parenthood Federation and Action Fund both serve as social movement

organizations (SMOs) in contemporary feminist movements

6

. Historically, Planned Parenthood

focused on issues that were representative of certain feminist ideologies and certain gendered

bodies. Specifically, Planned Parenthood focused on reproductive rights, such as the right to use

birth control, without also recognizing the structures (race, class, location, etc.) that limited

women’s access to birth control – legal or not. In this paper I examine PPAF’s health activism to

determine if Planned Parenthood is engaging with issues of intersectionality in two politically

different states. Specifically, I ask is Planned Parenthood engaging with issues of

intersectionality? And, if so, how are they doing this in two politically different states? Finally,

is Planned Parenthood centering reproductive justice?

These questions are significant because Planned Parenthood primarily serves women

whose daily experiences of being raced, classed, sexed, and gendered impact the way in which

they can and do receive care (Krieger and Smith 2004). In addition, certain women have more

agency, “autonomy plus options”, to decide if, when, and how to reproduce (Showden 2011).

Poor women, women living in rural areas, women of color, LGBTQ+ individuals, all face

structures (laws, norms, physical space) that limit their agency and their control over their own

bodies (Loyd 2014). These women also face histories of oppression, especially in regards to their

reproductive rights (Threadcraft 2016). I will determine if Planned Parenthood, in serving these

women, is attentive to that intersectionality, to the multiple layers of identity and politics that

oppress certain women’s reproductive choices and marginalize certain bodies. This goes beyond

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

5

Planned Parenthood is often a provider of life-saving care, especially through their STD and

cancer screening services, sex education, and treatment of various STDs (PPFA 2017).

6

SMOs are organizations whose mission aligns with that of a certain social movement.!

!

4

simply access to health care. These issues include providing access to safe housing, the ability to

leave abusive partners, the ability to keep and raise the children they do have without

succumbing to poverty or homelessness, the ability, generally, to exercise their civil rights in

their reproductive health and daily lives.

The second question

7

is particularly relevant today, at a time when political polarization

is heightened and when the two major parties have adopted oppositional stances on abortion:

pro-life (anti-abortion rights) and pro-choice (pro-abortion rights). Planned Parenthood is

especially vulnerable to attack and defunding in conservative (red) states, such as Missouri

8

, yet

in progressive (blue) states, such as Vermont, Planned Parenthood is well respected and

politically influential. Because of these differences in position, I analyzed Planned Parenthood’s

work in both a sympathetic and a hostile state – one red, one blue, from the same region of the

United States. In doing so, I determined how this political difference impacted Planned

Parenthood’s ability to engage and their actual engagement with intersectionality.

Finally, reproductive rights have been the center of many recent debates. Often, these

debates take the form that the national parties have: pro-life and pro-choice. But reproductive

health is far more complicated than pregnancy or abortion. While abortion is an issue in the

reproductive justice movement, it is not the whole story. Women have faced many other barriers

to their own reproductive choices: forced sterilization, lack of access to accurate sex-education,

lack of access to birth control, and more. Reproductive justice, then, includes reproductive rights

but also requires consideration of the other factors impacting access to reproductive health care

and individual’s ability to make decisions about their reproductive health. Because of Planned

Parenthood’s historical focus on rights, and their national image as an abortion provider (even

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

7

How does Planned Parenthood engage with intersectionality in two politically different states?

8

On May 10, 2018, the Missouri legislature voted to cut off Medicaid funding to Planned

Parenthood, which prevents Medicaid patients from receiving care at Planned Parenthood.!

!

5

though only 3-6% of their services are abortion related), I question if they can go beyond that

dominant narrative and bring issues of reproductive justice “from margin to center” (hooks

2000). I use this language of margins for two reasons. The first is that large SMOs and white

feminists “ignored the existence of all non-white women and poor white women” in their earlier

activism and advocacy, such that those groups were on the margins of feminist activity (hooks

2000:2). The second is that many issues of reproductive justice impact marginalized groups,

“[those] who are daily beaten down, mentally, physically, and spiritually – [those] who are

powerless to change their condition in life” (hooks 2000:1). To center these marginalized issues

and groups, then, is to focus on those issues, those people, and make reproductive justice the core

of an organization’s work and focus.

This case study is small and set in a specific location, but my findings are illustrative of

Planned Parenthood as a whole. Planned Parenthood health clinics serve vulnerable populations

nationwide, primarily women, who experience physical and emotional effects of intersectional

oppression. Is PPAF, the political arm of Planned Parenthood, pursuing politics that will serve

these patients – both in Planned Parenthood clinics and in their daily lives? How does the

political environment impact that engagement? Is Planned Parenthood centering reproductive

justice?

In this paper I begin with a brief history of feminist movements, paying particular

attention to Planned Parenthood’s evolving role within those movements. Next, I review

literature on the different ways scholars have engaged with social movements and how their

findings support my research questions. I then include a section on organizational composition,

this is primarily because Planned Parenthood has three main and deeply interrelated purposes:

health care, education, and advocacy. I focus primarily on advocacy in this paper, but in places

!

6

address the other purposes when they connect with advocacy. Then I describe my data and

methods, followed by an in-depth analysis of my findings. Finally, I draw conclusions and offer

directions for future research.

FEMINIST MOVEMENTS AND PLANNED PARENTHOOD

Planned Parenthood has been active in various feminist movements and campaigns since

it was founded more than 100 years ago. They are one large SMO situated in a long history of

feminism, and my questions, in particular, are grounded in that feminist history and evolution

9

.

In the early and mid 20

th

century, Planned Parenthood focused on establishing clinics and

providing accurate reproductive health care and education (PPFA 2018a). In the 1960s and early

1970s, Planned Parenthood began, along with many other feminists and women’s health

organizations, to focus on fighting for and providing political access to safe and legal abortions.

During this time, women’s health activists framed abortion as issues of rights and agency (Loyd

2014). White women – largely of the middle- and upper-classes – wanted control over their own

bodies, advocating for their right to choose if, when, and how to have children (Loyd 2014). In

1973, with the Court’s decision in Roe v. Wade, these women won a significant battle for

reproductive rights and choice

10

.

However, while Roe was upheld as victory of choice, a victory for women’s agency, it

was less so for poor women and women of color. Poor women, particularly poor women of

color, were “subject to coercive reproductive policies enacted directly on their bodies through

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

9

Intersectional feminism, which informs my questions, is a relatively new iteration of feminism

that has gained popularity in academia and public life in recent years. It offers a critique of other

feminist movements, as well as possibilities for more diverse and representative feminist activity,

both in the actions of organizations such as Planned Parenthood, and in individual actions.

10

Roe v. Wade (1973) is a Supreme Court case that extended the right to privacy to include a

woman’s right to have an abortion. It is regarded as the case that legalized abortion.

!

7

surgical procedures and the welfare system” (Loyd 2014:155). These policies included forced

sterilization, lack of access to safe abortions geographically and economically, and other

constraints for those dependent on the paternalistic welfare system. Women, particularly women

of color, began organizing in response to forced sterilization in the 1960s. Thus, while Roe

signified the right for women to choose to abort pregnancies, Relf v. Weinberger (1977) signified

the right for women to choose to have pregnancies

11

. Together, these two cases brought national

attention to the ways in which women’s bodies had been controlled by health care providers and

the welfare system, and they substantively extended agency to women in their own reproductive

health

12

.

These two distinct cases demonstrate the diversity of reproductive issues. Today, as in the

late 20

th

century, feminists are not always concerned about the same oppressive policies and

systems and thus do not always fight for the same causes. As white, elite women came to

feminism, they created a feminist movement that was based in their own experiences of sexual

oppression. Because women are moved to become feminists based on their own experiences

first, the various white, elite feminist movements neglected to attend to the experiences of

women who have different experiences of gender, class, sexuality, and race (Ahmed 2017). In

omitting these groups, this particular feminism suited white, elite women’s specific interests and

experiences (Reger 2017).

Because white women, along with the largely white feminist organizations they

constructed and run, were more visible in the media, their activism and successes were typically

prominently displayed and celebrated. The organizations they constructed, such as National

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

11

The Relf sisters, age 12 and 14, were both intentionally sterilized at a federally funded clinic in

Alabama without their consent. They won their case, Relf v. Weinberger (1977), before the

Supreme Court, legally ending the practice of forced sterilization.

12

This extension was limited, though, and forced sterilizations, for example, continued after Relf,

though at lower numbers (Loyd 2014).

!

8

Organization for Women (NOW), National Abortion Rights Action League (NARAL), and

Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA), represented these particular feminists – both

in their leadership and in their goals. This was, to some degree, precipitated by the demographic

makeup of the cities where these groups had offices (Reger 2012). Groups today have the

potential to be more attentive to, in particular, racial and ethnic diversity when they maintain an

ideology of inclusion as well as structural opportunity for leadership by women of color (Scott

2005). However, there is little evidence to suggest that racially diverse leadership necessarily

leads to changes in policy orientations and goals of those groups (Reger 2012).

By examining Planned Parenthood in two states, each diverse in unique ways, I explore if

this organization falls into the same patterns of past iterations, and if it diverges by engaging

with issues of intersectionality. Simply being aware of the diversity of their patients does not

indicate that an organization is centering those patients, people of color or LGBTQ+ individuals,

for example. However, in analyzing how this organization succeeds and fails to include non-

white, non-elite leaders and patients, I seek to reveal if and how they engage with

intersectionality and whether they are centering reproductive justice in that work.

LITERATURE REVIEW & THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

Planned Parenthood, in particular PPAF, is a large and influential SMO in the feminist

movement today. However, because they are often targets of attack and misinformation

campaigns, this organization is difficult to access for academic research

13

. But researchers often

study feminism as practice, or as a social movement, through examinations of SMOs – many of

which are similar to PPAF in their composition and goals. Reger and Staggenborg (2006), for

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

13

Planned Parenthood was recently the target of a misinformation campaign that stated that they

were selling fetal tissue in order to fund their services. This was incorrect, but (temporarily)

damaged the organization’s image and legitimacy.

!

9

example, study NOW leadership, tactics, and success through in-depth interviews with

organizers and activists. Research on SMOs demonstrates the ways in which organizational

strategies, tactics, goals, and ideologies shift in response to changing political opportunity

structures, as well as the broader social and economic context (Harnois 2012; Reger 2002). In

addition, research on SMOs can illuminate changes in the underlying movement.

Specifically, although many feminist movements had focused some energy towards the

acquisition of and protection of reproductive rights, the reproductive justice movement did not

emerge until the 1990s. Planned Parenthood, previously an SMO in the women’s movement,

broadly, adopted a place within the reproductive justice movement. Black women at the United

Nations International Conference on Population and Development coined the term “reproductive

justice” in 1994, and the movement itself originated shortly thereafter (Staggenborg and

Skoczylas 2017). The language of reproductive justice is often conflated with the abortion rights

movement, even though, as identified previously, these are not the same (Loyd 2014). As the

feminist movement progressed, women of color pushed for the more inclusive language of

reproductive justice, rather than abortion rights, to attend to women’s diverse reproductive

experiences based on their social and economic positions (Threadcraft 2016). As evidenced by

the evolution of movements for reproductive rights in the 20

th

century, the naming and

subsequent movement for reproductive justice has continued to broaden (Staggenborg and

Skoczylas 2017). The justice framing “led by women of color, strives to make explicit

intersectional connections to other struggles, linking reproductive rights to human rights

agendas” (Staggenborg and Skoczylas 2017:220). If Planned Parenthood is centering

reproductive justice, they are also making these connections, recognizing that reproductive rights

are intertwined with many other rights and issues.

!

10

The reproductive justice movement emerged at a time of relatively many political

opportunities

14

. Political opportunity refers, generally, to the “features of the political

environment that influence movement emergence and success” (Staggenborg 2011). Meyer

(2015) argues that social movements are episodic because these political features or structures

vary over time and space. Movements tend to grow when there are “greater political openings”

that enable activists to organize and mobilize safely and with the possibility for success (Meyer

2015: 39). These openings are not fixed and may be available to only certain organizations.

Planned Parenthood regularly has greater political opportunities in progressive (blue) states,

while typically facing constraints in conservative (red) states. This difference enables me to

examine how Planned Parenthood engages with issues of intersectionality in the face of two

different political opportunity structures, and to see to what extent this theory explains Planned

Parenthood’s activism.

According to Meyer (2015), “social movement organizations form to coordinate the

process of turning inchoate grievances into issues and apathy or dissatisfaction into political

action” (45). SMOs, then, are often the actors in social movements with the resources necessary

both to identify political opportunities and to respond with appropriate strategies and tactics.

SMOs, though, have varying structure based on the type, size, and ideology of the organization

(Ganz 2000; Staggenborg 1988). These different structures are oriented toward different

strengths and weaknesses, different tactical repertoires, and different levels of success and

longevity (Freeman 1973; Staggenborg 1988, 1989; Taylor 1989; Ganz 2000). Organizations

differ on two primary dimensions: level of formalization and level of centralization (Staggenborg

1988, 1989; Freeman 1973). More formalized SMOs have established decision-making and

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

14

!For example,!Bill and Hillary Clinton, both strong supporters of Planned Parenthood and

reproductive rights, were in the White House, offering more opportunity for Planned Parenthood

to engage in proactive political action.!

!

11

operational procedures, a division of labor by function, membership criteria, and formal rules

governing subunits (Staggenborg 1989). Formalized SMOs, in particular, are able to maintain

movement activity when faced with a lack of political opportunities (Taylor 1989; Meyer 2015).

In addition, formalized SMOs tend to have leaders who can offer institutional knowledge of

strategies and tactics, as well as maintain relationships with legislators or coalition partners, so

that the organization is able to respond when moments of greater opportunity arise. Planned

Parenthood is highly formalized, with many different levels and functions, and is able to

maintain that institutional knowledge, respond to changing political opportunities, and maintain

coalitions over time.

Coalitions are significant in helping organizations participate in collective action as well

as in creating networks of influence to maximize success. Coalitions typically form between

groups with similar interests, but there are no guarantees of successful formation or activism

(Staggenborg 1986). Coalition formation and sustainability is more likely between formalized

SMOs because these SMOs have professional staff able to act as organizational representatives

to coordinate and maintain coalition work (Staggenborg 1989). In addition, formalized SMOs are

able to pursue coalition work in one area, while using other resources to pursue their other tactics

or goals (Staggenborg 1986; Taylor 1989; Ganz 2000). Staggenborg (1986) argues that coalitions

typically form either to take advantage of opportunities and resources or to respond to threats. In

addition, the chances that a coalition will be successful depend on the likelihood of reaching a

victory. When victory is likely, “resources tend to be plentiful and organizational maintenance is

not threatened; consequently, shared goals are more salient than organizational maintenance

needs” (Staggenborg 1986:380). Planned Parenthood, in part because of its age and

institutionalism, has many coalition partners who share common ideology and goals. In

!

12

conservative states, these coalitions are especially important because resources for progressive

organizations, generally, are more limited and Planned Parenthood is able to build coalitions to

better use those resources and pursue their goals.

Today, reproductive justice activists, learning from past movements, “struggle with

building a diverse and inclusive movement, and they work in organizations and agencies founded

in the 1970s and 1980s geared at women’s lives” (Reger 2017). These feminist struggles appear

at different levels, and feminists find success in different ways. In those organizations founded in

earlier generations, these struggles happen at the individual and institutional level – redefining

and muddling categories (Butler 1990), breaking down walls and barriers (Ahmed 2017), and,

often, failing to incorporate diverse voices and intersectional ideology (Reger 2017). My first

research question, is Planned Parenthood engaging with issues of intersectionality, is designed

to look at how Planned Parenthood is engaged with this common feminist struggle.

Feminist theory has evolved over time in many different iterations, that sometimes

oppose and other times complement each other. Although the idea that feminism is the

movement for equality of women and men was popularized in the 1960s, many feminists have

critiqued this definition (e.g. Brown 1992; hooks 2000). Instead, “Feminism as a movement to

end sexist oppression directs our attention to systems of domination and the interrelatedness of

sex, race, and class oppression” (hooks 2000:33). Intersectional feminist theory, then, focuses on

the ways in which power functions to create identities and structures of oppression. Sara Ahmed

(2017) proposes that reflecting on how certain bodies are not accommodated by a world can

illuminate the consequences of our intersectional identities. Bodies that are differentially raced,

gendered, and classed experience various power structures based on the interaction and

convergence of those bodily experiences. Intersectional feminist theory involves examining the

!

13

ways in which various identity categories intersect to create structures of dominance and

privilege, and serves as a resource for studying the dynamics of power on bodies.

Kimberlé Crenshaw (1991) proposes, “identity groups in which we find ourselves are in

fact coalitions” (1299). As such, attending to “multiple dimensions of privilege and difference is

necessary to develop awareness about a whole spectrum of subordinated histories and struggles”

(Cho, Crenshaw, and McCall 2013:801). This knowledge can enable SMOs to form broad

coalitions, based in these diverse and often shared experiences of subjugation. Broad coalitions

then can serve as a form of intersectional politics, which dismantle “structures that selectively

impose vulnerability upon certain bodies” (Cho et al. 2013:803). Subsequently, broad coalitions

might offer a way “to dismantle the world that is built to accommodate only some bodies”

(Ahmed 2017:14). Planned Parenthood is part of many coalitions, some of which are a form of

intersectional politics; others are built to respond to a need or to achieve a specific goal.

The reproductive justice movement incorporates many of the earlier SMOs involved in

women’s and health activism. Planned Parenthood, as well as the various political and

educational arms of this organization, is one such organization that claims a place in the

reproductive justice movement. In this paper I will answer: is Planned Parenthood engaging

with issues of intersectionality? If so, how are they doing this in two politically different states?

Is Planned Parenthood centering reproductive justice? In doing this, I hope to offer a broad

analysis of an organization that is both an essential health care provider and a powerful and

important feminist SMO.

!

14

ORGANIZATIONAL COMPOSITION AND STRUCTURE

Margaret Sanger founded the first birth control clinic in the U.S. in 1916. This formed the

foundation of her later activism, as she opened the Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau and

incorporated the American Birth Control League both in 1923. These two organizations later

merged and became PPFA (PPFA 2018a).

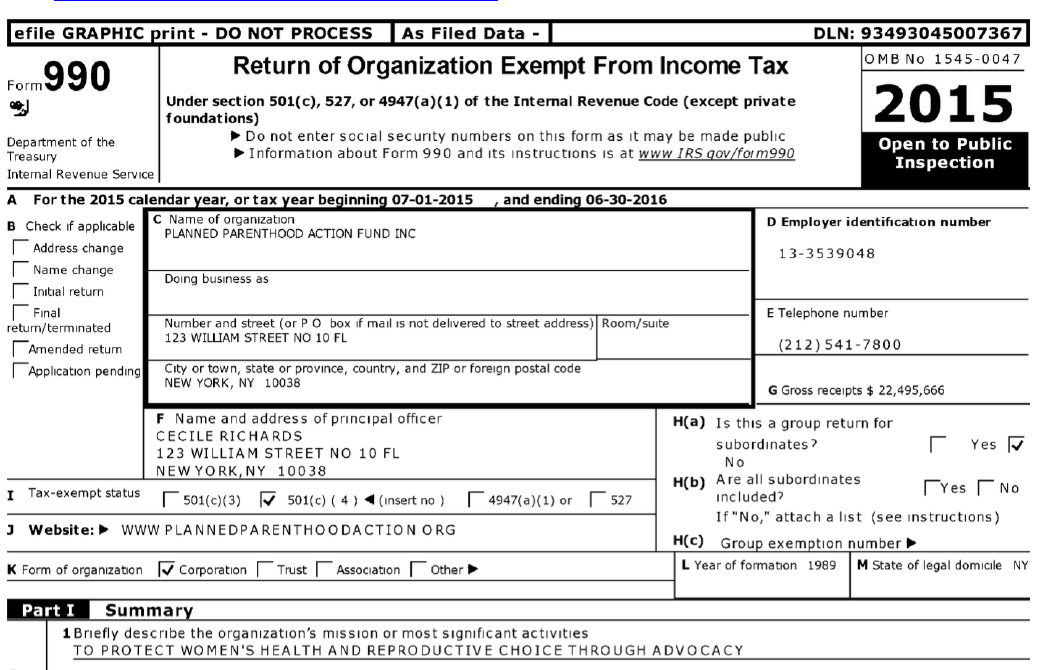

There are a few important distinctions to make between the various arms of Planned

Parenthood. The first is the difference between Planned Parenthood Federation of America

(PPFA) and Planned Parenthood Action Fund (PPAF). While both are non-profit organizations,

PPFA is a 501(c)(3) organization and PPAF is a 501(c)(4) organization. 501(c)(3) organizations

are broadly defined as charitable organizations, while 501(c)(4) organizations are commonly

defined as social welfare organizations (IRS 2018).

Because PPFA, in these early iterations, was primarily focused on providing health care

and education, it was classified as a 501(c)(3) organization. Because of this, PPFA was (and is)

limited in what and how much political activities it can conduct. PPFA may participate in some

lobbying, so long as it is not a “substantial part” of their overall activities. In addition, PPFA may

not participate – directly or indirectly – in any campaign on behalf of any candidate for elective

public office (IRS 2018). In line with these requirements, PPFA’s mission states:

Planned Parenthood works to educate and empower communities, provide quality health

care, lead the reproductive rights movement, and advance global health. Planned

Parenthood believes sexual and reproductive health rights are basic rights. (PPFA 2018b)

This mission includes political advocacy, but it is not a substantial part of the overall activities.

PPFA, then, is primarily focused on reproductive health care and education.

When Faye Wattleton, the first woman of color to be president of PPFA, founded PPAF

in 1989 she did so with the intent that it be the political advocacy arm, engaging “in political

!

15

education campaigns, grassroots organizing, and legislative and electoral activity” (PPFA

2018b). She knew Planned Parenthood would have to be more political in order to keep its doors

open and provide care. Therefore, PPAF is classified as a 501(c)(4) organization so that it can

pursue lobbying as its primary activity to further social welfare without jeopardizing its tax-

exempt status. In addition, PPAF may engage in some political campaigns, so long as that is not

its primary activity (IRS 2018). As such, PPAF’s mission is:

To protect informed individual choices regarding reproductive health care, to advocate

for public policies that guarantee the right to choice, as well as full and non-

discriminatory access to reproductive health care, and to foster and preserve a social and

political climate favorable to the exercise of reproductive choice. (PPFA 2017)

Today, as in 1989 when PPAF was founded, it is focused on protecting access to reproductive

care and choice. These three aims – health care, education, and advocacy – are foundational to

Planned Parenthood’s various bodies and complement one another at local, state, national, and

international levels.

There are both 501(c)(3) and (c)(4) organizations represented in this study. Any affiliate

of PPFA is a (c)(3); similarly, any affiliate of PPAF is a (c)(4). In this study, I examine one

regional affiliate of PPAF, as well as two local affiliates of PPFA within that same region. There

are two national PPFA offices (one in New York, the other in D.C.) and 56 affiliates of Planned

Parenthood, at least one in each state. In addition, there are more than 650 local Planned

Parenthood health centers nationwide. PPAF has regional, state, and local affiliates. The regional

affiliates typically have different staff for each state in that region. In addition, local affiliates are

primarily present in large states, such as California. In analyzing this data I will be very clear

about which organization type and level I am referring to.

!

16

DATA AND METHODS

In this study I use data from in-depth interviews (N=6) that I conducted from February

through May 2018. These interviews were with two current (at the time of the interviews)

Planned Parenthood Action Fund (PPAF) employees, and four past Planned Parenthood

Federation of America (PPFA) and PPAF employees. In addition to this data, I relied on archival

data from organizational websites and tax histories. Together, this data enabled me to answer my

research questions: is Planned Parenthood engaging with issues of intersectionality? How are

they doing this in two politically different states? Is Planned Parenthood centering reproductive

justice?

I used two key contacts, one past activist and one current activist (at the time of the

study), who were able to each give me access to additional interviewees. This snowball

technique was necessary and became intentional because Planned Parenthood, generally, is a

difficult organization to access. In particular, this is because of the strong and often violent

countermovement activity that directly targets their organizations and activists. Emails from

unknown sources are often phishing scams from opponents seeking to attack Planned

Parenthood. As a result, in my initial recruitment emails I only received one positive response.

That response was from an activist in a state that is friendly to Planned Parenthood, both in the

legislature and in the culture more generally. From branches in other states, where Planned

Parenthood faces more attacks – both physical and otherwise – I received only negative or non-

responses to requests for interviews.

Because of the organizational concern to maintain security for patients and activists, I

used snowball sampling and increased anonymity measures. Using the two key contacts I

developed, I was able to expand the scope of my study to examine the consequences of political

!

17

differences in the coalition work, goals, and successes of different branches of Planned

Parenthood. The two key contacts I facilitated were a current activist from a (blue) state with

great political opportunities and sympathy for PPAF’s work, and a past activist who worked in a

(red) state with few political opportunities and often hostility for both PPFA’s an PPAF’s work.

After obtaining contact with my initial sample, I conducted in-depth interviews with each

of the subjects I identified through my snowball sample. The respondents I sought were from

politically different states (red, blue), and those from the past were from the same general time

period. The red state in my analysis has a Republican governor and there is a Republican

supermajority (greater than 80%) in both the state House and Senate. In addition, in the last

legislative session two pieces of anti-abortion legislation were proposed, which directly target

Planned Parenthood and impact their ability to provide this service. The red state is also

conservative, both in terms of their politics and legislation. In the blue state, the governor is a

Democrat, there is a Democratic majority (greater than 50%) in both the state House and Senate,

and there have been no negative bills targeting Planned Parenthood proposed in the past

legislative session. The blue state is generally more progressive in their politics and legislation.

The past activists worked during the Bush and Obama administrations, both of which

were generally more supportive of Planned Parenthood’s mission (the latter substantially more

so). The current activists, at the time of the interview, were working within the scope of a

Republican dominated national legislature and a Republican presidency. I chose these two

national moments and selection of red and blue states for their distinct political differences

(political opportunity opposed to political constraints), and the ways in which those differences

at the national level impacted state and local level Planned Parenthood activism and functioning.

!

18

Interview questions addressed the nature of the activist’s participation in the organization,

strategies and tactics, issues, and goals and successes of organizational activities (see Appendix

A). While their mission speaks to reproductive justice by incorporating language of racial and

economic justice, I used in-depth interviews to see if they are actually engaging with these issues

at the state and local level, and how individuals within the organization understand and seek to

further that cause. In addition, each interviewee had a unique view of the social world, and that

context added depth and meaning to their responses. Finally, I conducted interviews because

they “bring human agency to the center of movement analysis” (Klandermans and Staggenborg

2002). As such, my analysis is grounded in each respondent’s language and personal

understanding of the issues at hand.

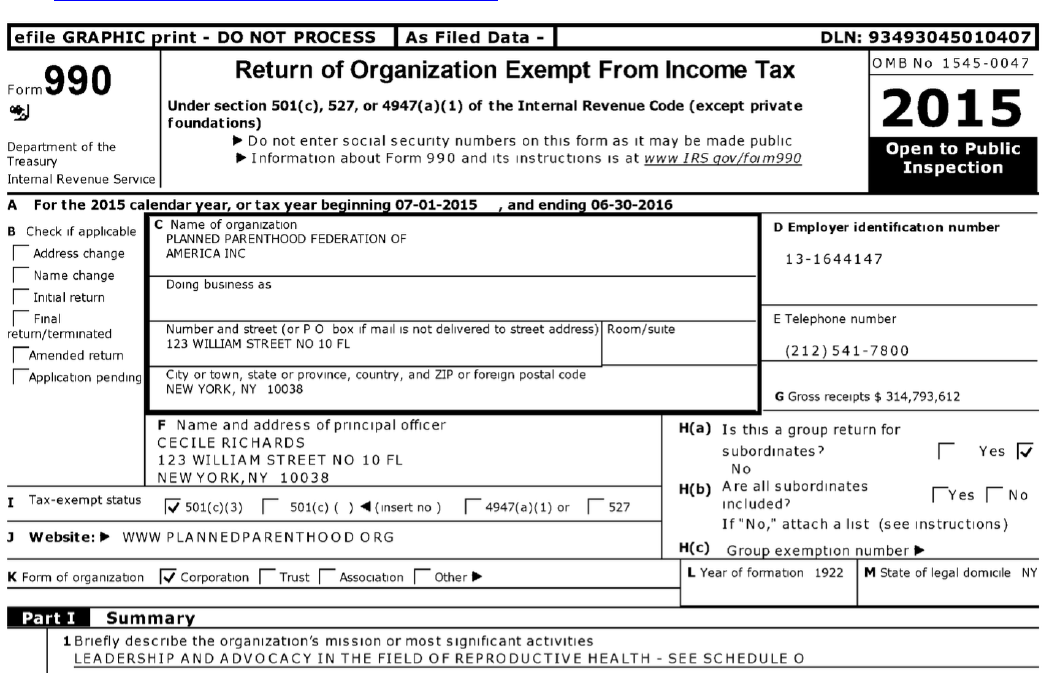

Because of the limited size and scope of my interview sample (N=6), I supplement this

data with archival reports. In particular, I examined tax data (IRS Tax Form 990), recent

organizational financial reports, and website data (both past and present). These documents are

all publically available and provided information on the organization structure of PPFA and

PPAF, and current and past organizational activities and events (see Appendix B). Together, this

data assisted my analysis of the structural barriers Planned Parenthood faces and the changes the

organization has made over time, as well as supplemented my interview data where interviewees

could not recall specifics about events or legislation. I recognize that the six individuals I

interviewed are not a representative sample of activists or branches of PPFA or PPAF. However,

these activists and the issues they address are illustrative of the larger national context.

In compiling my data, I identified patterns, differences, and changes over time. In

particular, I looked at the differences between organizational activities in red and blue states, and

at times of high and low political opportunities. I also looked at how issues of reproductive care

!

19

and reproductive justice have changed over time. My analysis is centered on how Planned

Parenthood has shifted their focus from reproductive rights more narrowly to reproductive justice

more broadly, and what political barriers and aids enable or deter these shifts in two different

states.

ANALYSIS

Our work this session, we could describe it as being like, ‘drawing a pink line around [the

state]’, and defending our state from whatever nonsense the federal government tries to

throw at us. (Current PPAF Public Affairs Manager, Blue State)

We have to celebrate those small victories to be able to keep morale up and kind of see

the progress that we’re making. (Current PPAF Public Affairs Manager, Red State)

The political environments in these two states are vastly different. The current PPAF

Public Affairs Manager from the blue state (Blue PAM; for descriptions of each interviewee see

Appendix C) reflected on the defensive, resistance work they’re doing at a national level, but

also noted the strong state-level support for Planned Parenthood that enables her office to engage

in this national work because they’re not facing attacks within the state. Instead, she uses her

resources to pass proactive legislation to expand women’s access to birth control and to protect

residents from actions of the national government. In the red state, though, the current PPAF

Public Affairs Manager (Red PAM) faces a hostile legislature that constantly seeks to undermine

Planned Parenthood’s work and limit access to abortions and other essential care. In this state,

getting proactive legislation even proposed is a time-consuming and often futile goal. Instead,

she focuses her energy on fighting against state legislation that would negatively impact Planned

Parenthood, women, and other marginalized groups.

In my analysis, I focus primarily on Planned Parenthood’s advocacy, because it is in their

advocacy work that I can see political patterns and changes over time. The past activists framed

!

20

issues of health care and education within a very different political moment than those currently

working for PPAF, resulting in different forms of advocacy and different focuses in that work. In

addition, Planned Parenthood serves patients in their health clinics who face intersectional

structures of oppression, but I’m curious to determine if and how they engage with those issues

in their political advocacy. Similarly, only at (c)(4) Planned Parenthood offices (i.e. Action

Fund) can that advocacy work be a substantial portion of their overall activities. So I

intentionally selected my sample, being primarily from PPAF affiliates, in order to see how these

advocates deal with intersectionality in their legislative and political work.

Purpose: Providing Health Care

The purpose of an affiliate offers the blueprint for their activism. In Red Past 1’s PPFA

office, the main purpose was to provide health care. Doing so was at the center of the advocacy

work she did as a community organizer. Similarly, Blue PAM noted that the purpose for her

state-level PPAF affiliate was,

To advocate for our mission in advancing reproductive health rights and justice locally,

and then regionally and nationally as applicable. So our main focus is to ensure that

voters are aware and acting upon those issues.

Health care, then, in the blue state is still centered, but they do this through engaging voters on

issues of health policy. Meanwhile, in the red state, Red PAM articulated the purpose of her

position slightly differently.

Definitely to try to, you know we have that long-term goal of breaking the supermajority

in [this state]. I’m also there as a stopgap between an extremely hostile legislature and

their efforts to try and close the doors of our health centers in [this state]. So, I’m there

both to advocate for and lobby for good policy and stop bad policy, and also, at the same

time, get friendlier folks elected so that we don’t have to spend so much time and energy

fighting against bad policy.

She is also focused on health care, but she expresses this focus by preventing politicians from

trying to “close the doors” of Planned Parenthood clinics. She has to spend much of her time

!

21

fighting against these attacks, so the purpose in the red state is far more defensive than

proactive

15

. Red Past 2 said the purpose of the state-level PPAF office he directed was, simply,

“to avoid negative legislation”. This is very similar to Red PAM’s remarks about constantly

being on the defensive. In a red state, Planned Parenthood has to focus on health care by

defending it, rather than increasing and supporting it.

Blue Past 1, who worked only for PPFA, focused on health care in her description of its

purpose.

To provide health care for people who needed it, with a focus on reproductive health

care… Keeping people healthy and serving low-income or marginalized people who

don’t have access elsewhere [to healthcare].

This aligns well with the national PPFA purpose and is appropriate for the (c)(3) status of the

office she worked for. In addition, she spoke specifically to the patients that Planned Parenthood

serves, “low-income or marginalized people” who rely on Planned Parenthood health centers for

their health care – reproductive and otherwise. These patients are often those receiving Title X

funds, who are on Medicaid or other public insurance, or individuals who cannot access care at

other locations for a variety of reasons. Her remarks are neither proactive nor defensive, but

speak more to the actual day-to-day work of Planned Parenthood health centers nationwide.

In addition, both Red Past 1 and Red Past 2 noted that when they worked for PPFA their

purpose was to serve patients. Red Past 2 told a story about getting a patient across state lines to

access an abortion, which was not technically a responsibility of a field organizer, but he knew

she was poor, and would not otherwise be able to get the care she needed. He concluded by

noting that the purpose of his affiliate was always “to get people care when they needed it.”

These interviews revealed that PPFA prioritizes the provision of health care to their patients –

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

15

I describe the two different types of advocacy work as “proactive” and “defensive” because

that is the language that all my interviewees used.

!

22

both in red states and blue states. In red states the stakes for centering patients are higher, and

might include crossing state lines, providing care for free, or accompanying patients to local

hospitals to advocate for them there. But each of the activists I interviewed spoke to the essential

nature of this work.

It is because of these different political environments that I ask both, is Planned

Parenthood engaging with issues of intersectionality? And how are they doing this in two

politically different states? The political differences greatly impact what goals PPAF sets, as well

as the extent to which PPAF pursues those goals to reach success. To answer these interrelated

questions about intersectionality and political opportunity, I draw on and interpret the language

and examples my interview subjects offered. Similarly, to answer my third question, is Planned

Parenthood centering reproductive justice, I analyze and interpret the importance of the various

stories that each of my interviewees shared with me.

Evidence of Intersectionality

Planned Parenthood is attending to intersectionality in a few ways in their advocacy

work. As evidenced with interview and archival data, Planned Parenthood forms coalitions with

other progressive groups, whose interest is not necessarily women’s health, to further goals

beyond reproductive health care. In addition, they focus on issues and bills that will impact their

patients in a variety of ways, in and out of Planed Parenthood health centers. Finally, underlying

each of these moves, Planned Parenthood is centering patients. They raise up patients’ stories

and experiences, considering how their activism, their work, impacts their patients and how to

serve these communities.

In each of these areas, Planned Parenthood is, at some level, engaging with questions of

intersectionality. As noted below, Planned Parenthood looks at intersectionality in terms of how

!

23

gender and race, or gender and class, or gender, race, and class intersect to impact their patients

and others in their states. They consider questions of gender normativity and heteronormativity,

and they seek to expand the categories included in “women’s health” to attend to these various

intersectional identities, questions, and needs. In Table 1, I consolidate this evidence of

intersectionality in terms of Planned Parenthood’s coalition partners, the issues they engage with,

and their work to center their patients.

Table 1. Evidence of Intersectionality.

Intersectionality

Coalitions

Issues and Goals

Centering Patients

Broad

Focused on various structures

that impose intersectional

oppression

Diverse

Issues ranging from trans

rights, to immigrant rights, to

equal pay, and more

Intentional

Building trust and listening to

determine the needs of the

communities they serve

Coalition partners. In their coalition work, Planned Parenthood is attentive to the various

ways in which gender intersects with other aspects of identity to constrain and impact bodies.

Red PAM noted that “If there is a social justice or progressive organization in [our state] we try

to work with them, because, again, pooling our power is the best way we can create change in

such a conservative state.” Thus, by forming coalitions, Planned Parenthood is able to pool

scarce resources rather than competing for them. Red PAM offered a specific example, their

coalition with Add the Words, “an organization that’s been working to update [the state’s] non-

discrimination legislation to include sexual-orientation and gender identity so that gay and trans

[residents] cannot get fired or lose their housing for being gay or transgender.” Red PAM

proposed that, though it is challenging to pursue this goal, the organizations work together so

they continue to make slow progress.

!

24

I’m not gonna not work on Add the Words, that’s just a near and dear and personal issue

for me and so that’s always going to be on my list of goals because its something that I

see as a need in the community, but I know that that’s gonna be a long-term goal…

because I am aware of the political realities of the state. (Emphasis hers)

She has to be attentive to the political responsiveness to an issue regarding LGBTQ+ rights, and

recognizes that this won’t change overnight. But by maintaining a coalition with Add the Words,

the issue remains salient in the progressive circles in this state. It is something that, while PPAF

cannot dedicate too many resources to this coalition, they can assist, as they are able, to create

change in the long term.

This particular long-term coalition with Add the Words is an example of Planned

Parenthood’s engagement with intersectionality, particularly regarding questions of gender

normativity and heteronormativity. Specifically, by doing this work, they are able to consider

how gender normativity impacts their patients and people in this state. In engaging with these

questions and this coalition, PPAF can better attend to the needs of LGBTQ+ individuals in their

advocacy, as well as in their health care and education programs. By acknowledging the ways in

which gender normativity functions to constrain certain bodies, Planned Parenthood is better able

consider how gender and sexuality intersect to marginalize certain communities and then to

center those communities’ needs and their stories in their advocacy.

By contrast, in the blue state, Blue PAM described far more diverse coalition partners,

with interests ranging from women’s health to voting rights to homelessness. One example she

offered was their work with “Mom’s Rising and the Economic Opportunity Institute… we’re

standing in solidarity and support with them so we’re trying to pass equal pay across [the state].”

She noted, “We are proud coalition partners with many, many different organizations. So it

really just kind of depends on time of day and what campaign we’re doing.” This comment

demonstrates the political openness to progressive causes: there are many progressive

!

25

organizations in this state, many with a focus that complements PPAF’s, and resources are less

scarce and can be shared more easily among more groups. In addition, working with multiple

partners enables PPAF in this state to pursue goals beyond reproductive health, goals that are

deeply tied to reproductive justice issues, but less explicitly so.

Many of the activists, both present and past, mentioned women’s rights groups as

common coalition partners. Blue PAM said, “We’re also almost all the time aligned with

different women’s rights groups. Like, kind of our usual folks that we’re always hanging out

with, like Legal Voice or NARAL, and so on.” These coalitions are “usual” in that PPAF has

been partnering with these organizations for much of their history and they work together

because of their similarities in missions and composition. However, most activists mentioned

these groups almost as an afterthought, typically following a list of other, more diverse

organizations. This indicates that as PPAF has expanded their mission they are actively working

to engage with wide-ranging issues that involve questions of intersectionality. By expanding

their coalition partners, PPAF is able to expand their focus and to consider additional

intersectional questions and structures, to see what changes are needed – in policy, health care,

education, and in the organization itself – to respond to their coalition partner’s interests and

needs. But they maintain these older coalitions in part because their missions are so deeply

interrelated and in part so they can also share resources with more groups.

In both red and blue states, deciding what organizations to form coalitions with is a

matter of finding organizations whose mission aligns with that of Planned Parenthood. However,

as previously mentioned, PPAF has expanded their mission and, as a result, has expanded the

criteria for coalition partners. In the red state, PPAF has diverse coalition partners, but they have

to be careful in how “loud and proud” they are about some of these. Red PAM noted that the

!

26

limited resources for progressive causes and constant attacks directed at Planned Parenthood

limits their overt coalition work.

Everybody has competing interests, and yet also a shared interest, but you have to come

at that shared interest with your organization’s best interests in mind… You know, it’s

just a lot of competing interests and there’s – it’s not like [our coalition partners are]

doing anything wrong, they’re doing things that are in their organization’s best interest.

This quiet and careful coalition work speaks to Planned Parenthood’s need, in red states, to

protect their image and, at least publically, work for their mission more narrowly.

Unlike in blue states, in red states PPAF has to be more careful about how they do this

work. This is largely because, in red states, PPAF has to preserve their resources and influence to

fight to strict anti-woman, anti-choice legislation that they face every legislative season. But, as

Red PAM told me, they do form coalitions with conservation groups, immigrants rights groups,

and more. They may have be quiet, but PPAF is still making a concerted effort to engage with

issues regarding how environmental concerns intersect with gender, issues regarding how race

and gender intersect, and issues that examine even more complex relationships between politics,

policy, and bodies. In addition, as Red PAM said, they come to coalitions with their best interests

in mind. By building these coalitions, even ones invisible to the public, PPAF is acting in their

best interest: expanding their mission and scope to engage with issues of intersectionality,

expanding their advocacy and centering those communities they already serve in their health

centers.

PPAF’s dedication to coalition work, even in the face of political hostility, demonstrates

their recognition of the importance of this work in following their mission. Red Past 1 noted that,

because many other progressive organizations are facing the same political environment, they

pool their resources. She spoke about a “bill that would’ve targeted or would have made it illegal

to text while driving” that could have enabled racial profiling. At first glance, PPAF’s opposition

!

27

to a texting bill seems far afield from their mission. Yet, in that case, they used their volunteers

to help block this legislation because they understood that that bill would have impacted certain

bodies, black and brown bodies, and further threatened already vulnerable populations

16

. This

example demonstrates PPAF’s engagement with issues of the intersection of race, immigration

status, and gender in their coalition work. Specifically, they can acknowledge that racism enacted

through racial profiling has significant health impacts

17

, and can directly impact individuals’

ability to access health care and live healthy lives.

This mutual relationship, of sharing volunteers and knowledge, is at the core of coalition

work. Although every progressive organization faces some level of insecurity and hostility in the

red state, they cooperate, sharing what they can and helping, as they’re able – even if they have

to be silent partners. This dedication to work together on issues beyond the many bills attacking

abortion rights is in part due to personal convictions, such as Red PAM’s dedication to Add the

Words, but also due to a recognition that any attack on civil rights is an attack on health care and

health more broadly.

In blue states, PPAF is also attentive to which organizations share their mission and

focus. Blue PAM described their current focus and how it impacts coalition building.

We care really deeply about pursuing reproductive justice and racial equity. So

increasingly, we’re endeavoring to do more to prioritize people of color led and centered

organizations in our work, that’s one of our priorities.

This focus on racial equality is evidenced on PPAF’s websites – both at the national- and state-

level. In their 2016-2017 Financial Report

(Planned Parenthood 2017), Planned Parenthood

affirms what Blue PAM noted.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

16

!She spoke particularly about immigrant populations in her description of who would be at risk.

17

These health impacts include greater levels of stress, leading to clogged arteries and early

death.

!

28

Planned Parenthood continued to build and strengthen relationships across movements to

protect access to health care with a deeper commitment to elevating the intersections of

reproductive health, rights, justice, and other issues affecting the communities we serve.

Planned Parenthood believes everyone should have access to health care, no matter what

– but far too often, systemic barriers, including the harmful legacies of oppression and

white supremacy, stand in the way of achieving health equity for all. Full access to health

care starts with strong, healthy, and supported communities.

This declaration, along with Blue PAM’s comments, could be empty. However, the coalitions I

described offer evidence of this work and attention to intersectional and structural impediments

to health care access in the communities they serve in red states, blue states, and nationwide.

Planned Parenthood is intentionally seeking coalition partners who represent the

communities they serve in their health centers. They recognize that supporting these

communities is necessary in order to protect their access to health care and their self-

determination. They do this by partnering with groups such as LGBTQ+ organizations and racial

justice organizations, whose members know the needs of the communities they represent.

Planned Parenthood can then assist these groups while also learning from the very people they

serve how to do this work better. They attend to the various structures that limit access to health

care based on the intersections of, for example, race and gender, and seek to deconstruct those

structures by engaging in coalition work.

Issues and goals. In part because of the time of year during which I conducted interviews,

the current activists spoke primarily about electoral work. When I conducted my interviews, the

legislative session in the red state had recently concluded, and Red PAM was engaged in

electoral season, in preparation for primaries in early May. Similarly, when I interviewed Blue

PAM, her legislative season was wrapping up, with only a week and a half left in the legislative

session. She was focused on that, while also looking ahead to the electoral season that would

begin for her as soon as the legislators adjourned. The past activists spoke more to legislative

!

29

work, but together, their work during these two seasons demonstrates Planned Parenthood’s

relationship to public policy.

Blue PAM offered a long list of legislative items that PPAF had brought to the legislature

or was supporting in the legislature. Some of these were directly related to the central purpose of

providing reproductive health care, while others were not. She described one significant package

during the legislative season.

One of our priorities was the Voting Justice Legislation that has been going through,

there’s four different bills. One is a Voting Rights Act, which has to do with basically

helping cities to enact districted elections so that city council members, for example,

can’t just all be at large; they have to be more representative of more areas of the city –

coming from different parts of the city. There’s also automatic voter registration, which

has to deal with, instead of you opting in to get registered to vote when you get your

license, it’s just an opt out. Same day voter registration or extending the period within

which you can register to vote, and then pre-registration for 16 and 17 year olds. So that

whole package is making good progress, but we’re looking to coalition partners to let us

know – the ones who are really the leads on it – to let us know if it’s in trouble or

anything like that and we chime in when we can.

This Voting Justice Legislation was a priority, but, as she mentioned, PPAF was not taking the

lead on that. Their coalition partners are taking the lead, but, because PPAF has more resources

and political recognition in the blue state, she can lend resources and aid as necessary. This

legislation is not directly related to health care, but it is related to health policy and civil rights.

Specifically, the voting rights portion would guarantee more direct representation of

communities on city councils. This potentially protects politically marginalized groups,

especially from smaller neighborhoods or poor neighborhoods that often lack representation, and

gives them more voice on city councils. This encourages self-determination and provides a

platform for increased political participation from disenfranchised and marginalized populations.

Similarly, the various voter registration portions – automatic registration, same-day

registration, and pre-registration – would likely increase voter turnout and political participation.

!

30

Removing barriers to voting is essential for increasing participation and policy engagement.

Planned Parenthood serves these marginalized communities in their health centers, which

increases their agency in deciding when and how to receive health care. By increasing these

patients’ access to politics, these bills would also increase their agency in their political lives.

Given PPAF’s ability to propose legislation and devote resources to issues beyond abortion and

birth control, they can focus on issues that are related and deeply impact how marginalized

groups engage in politics.

However, because PPAF’s mission is “To provide women’s health and reproductive

choice through advocacy”, this state-level branch is also engaged with legislation that impacts

women’s health. Blue PAM described the Reproductive Parity Act, which deeply impacts

reproductive health.

The Reproductive Parity Act, that’s one of our top pieces of legislation, we’ve been

working on it for at least like 5 years. That would mandate that all insurance plans in [this

state] cover abortion care along with a broadened range of contraception. Instead of a

plan saying, like, ‘oh, you can only have this one kind of birth control’, saying all FDA

approved methods should be approved without a copay.

The Reproductive Parity Act is more obviously related to PPAF’s mission. However, it is a

broadly pro-choice piece of legislation. I say “broadly” to distinguish this bill from the strictly

pro-abortion bills that the activists from the red state lauded as victories (although, really, these

victories tended to be defeats of anti-abortion legislation). This bill does protect a woman’s right

to access an abortion, expanding that right to make it more accessible to women with limited

income or substandard insurance coverage, but it also increases access to more diverse forms of

birth control. Some women cannot use certain forms, and some women simply prefer certain

forms of birth control. This legislation would protect women’s right to make that choice with

their doctor and would guarantee coverage. This extends the birth control provision of the ACA,

!

31

a victory that several of the past activists I interviewed held up as a momentous victory for

women’s health and women’s rights.

The Reproductive Parity Act, in its breadth, is another example of Planned Parenthood’s

consideration of intersectional needs. In particular, by advocating that insurance plans cover

abortions, PPAF recognizes that abortion access is limited by economic standing. Women who

are from the middle and upper classes might be able to afford an abortion, even without

insurance, but women from lower classes, women who are more likely to seek abortions, are less

likely to be able to afford them. Similarly, by requiring insurance coverage for all forms of FDA

approved birth control women would be able to make unconstrained choices about their

reproductive health. This increases women’s agency immensely, making every birth control

choice – including abortion – a viable option for women.

In addition to this more strictly women’s health bill, Blue PAM mentioned the

Reproductive Health Access For All Act, which did not make it out of committee this year.

That bill would have been kind of similar to the Reproductive Parity Act, but it would

have been far more inclusive, because it also would have included things like STD

screening testing and treatment and counseling, and breast feeding support and services,

and gender affirming hormone therapy for trans individuals, and would also include

coverage for undocumented immigrants, and so we’re really disappointed that it didn’t go

further this year. It would do more and be more inclusive for all, but it’s gonna be a huge

priority next year.

As she says, this bill would have expanded access to many varied reproductive health services.

The various components demonstrate different ways in which reproductive health care can be

different for different bodies. For example, the provision for hormone therapy for trans

individuals demonstrates recognition that trans rights are reproductive rights, and that PPAF is

attentive to how gender identity and sexual orientation intersect to marginalize trans individuals.

In addition, this provision demonstrates that PPAF is committed to dismantling “structures that

!

32

selectively impose vulnerability upon certain bodies”, in this case, trans bodies (Cho et al.

2013:803).

While Planned Parenthood has historically focused on women’s rights, with a narrow

definition of women, Blue PAM spoke to their focus on non-heteronormative gender and sexual

identities and rights. Similarly, Planned Parenthood health clinics serve undocumented

immigrants, individuals who otherwise would not be able to access health care, and the provision

providing coverage to undocumented immigrants suggests that Planned Parenthood is trying to

serve this population both in its health centers and in the legislature. Specifically, this group is

entirely disenfranchised from the voting process in the United States, so PPAF, along with

various other SMOs, are able to help move this group from margin to center, raising up their

voices and focusing on their needs in their legislative work. Their dedication to this bill, with it’s

many provisions demonstrate Planned Parenthood’s dedication to their diverse patients, patients

who experience marginalization based on their various identities: sexual orientation, race,

immigration status, and more.

Centering patients. Planned Parenthood clinics are the main vehicles for providing health

care, but they also incorporate health education and advocacy. For example, several interview

subjects described the Health Center Advocacy Program. The HCAP involves “[talking] with

patients and find out a) how we can better serve them but also b) how we can better let them

know what’s happening in their communities” (Red PAM). It is a chance for PPAF activists to

“talk with people face-to-face about the public policy issues that are happening that could impact

their ability to even be in that waiting room” (Blue PAM). The HCAP is a way for Planned

Parenthood health centers to determine their patients’ health care needs, to educate and inform

patients about policy issues, as well as bring patients stories into their advocacy work. By doing

!

33

this work, PPAF can begin to see how the intersections of race and gender, for example, impact

health care and how policies impact different raced and gendered bodies.

Because Planned Parenthood clinics serve vulnerable populations, I was curious how

PPAF attends to the needs of these diverse populations and various barriers to health care in their

advocacy work.

I think probably the biggest way that we [attend to the diverse population in our state] is

by trying to be increasingly centered around our patients, because we know that we are

not truly meeting our mission if our patients, and their needs and concerns, are not being

lifted up first and foremost. We know that they are representative, often, of some of the

most marginalized populations in the state, and they come from all walks of life, of

course. For those who see us the most regularly, we’re often the only health care provider

they ever see and so they’ve become the people we want to center. (Blue PAM)

Centering patients is essential work for an organization such as Planned Parenthood because

their patients are precisely those communities that face “systemic barriers, including the harmful

legacies of oppression and white supremacy” (PPFA 2017) and those communities that are the

most politically and socially marginalized. In order to center patients, PPAF implemented the

HCAP program, which enables Planned Parenthood, as an SMO with political legitimacy, to

deploy their political influence to amplify the voices of their patients and center their needs in

their advocacy work.

Giving legislators these stories can demonstrate how the policies they pass can impact

their constituents in deeply personal ways. For example, Red Past 1 mentioned that she spoke to

a patient in reference to bill that allowed doctors to deny patients based on religious reasons. The

patient had been experiencing a lot of bleeding after giving birth, which can be life-threatening.

And she was bleeding, and she was given a prescription, and the health care provider

called the Walgreen’s to fill that prescription… Anyway, so this woman could not get her

prescription filled at Walgreen’s because the person there said, ‘I can’t do this for

religious reasons’… So the woman had to actually go to an alternate pharmacist and get

that filled. And that was a life-threatening event. So, she could have died.

!

34

This story drew attention to a flaw in a law that was designed to protect religious beliefs and

practice but had deeply negative consequences for this woman. And this story was just one

example. Red Past 1 went on to describe how the existing law also enabled pharmacists or

doctors to refuse to treat HIV positive patients, because they believe that HIV is God’s

punishment for being gay. So overturning this law benefitted not only women seeking life-saving

care or women seeking a Morning After Pill

18

, it also benefitted many LGBTQ+ people, as well

as women who might contract HIV from positive partners. Although the bill, on the surface, is

intended to protect religious belief – such as preventing a pharmacist from filling a prescription

they believe will lead to an abortion, when they believe abortion is wrong for religious reasons –

these stories, from women, from gay men, from patients, reveal how detrimental such a law can

be to certain bodies, especially those who are gendered and sexed in particular ways.

Planned Parenthood uses HCAP to bridge the gap between health care and policy by

sharing stories, such as this one, to demonstrate how lawmaker’s impact their constituents’ lives

and bodies through the legislation they push and pass. PPAF center patients’ stories in their

advocacy, recognizing that Planned Parenthood exists, at the most fundamental level, to provide

care to those patients – at health clinics, through educational programs, and through advocacy.

In line with this work, Red PAM spoke to her personal commitment to Add the Words. In

forming a coalition with Add the Words, PPAF is able to attend to the distinct structures that

limit LGBTQ+ individual’s ability to access health care. PPAF is becoming increasingly

attentive to issues impacting this community, both through specific bills, such as the religious

protection bill mentioned above, but also through coalition work with government agencies.

!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

18

Red Past 1 noted that people in “very conservative places consider the Morning After Pill to be

abortion, too… even though its not because its preventing a pregnancy. So, the definition of a

pregnancy is a fertilized egg that’s implanted into the uterine wall, and the Plan B or the Morning

After Pill prevent implantation, so its not technically pregnancy.”

!

35

We partner with different agencies within the Department of Health and Welfare to help

– you know, right now we’re working on a program to better serve the LGBTQ

population in Idaho specifically for intimate partner violence, because we’ve noticed that