SMU Law Review SMU Law Review

Volume 71 Issue 2 Article 4

January 2018

The Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign Provisions in Texas Oil The Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign Provisions in Texas Oil

and Gas Leases and Gas Leases

T. Ray Guy

Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Jason Wright

Weil, Gotshal & Manges

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

T. Ray Guy & Jason Wright,

The Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign Provisions in Texas Oil and Gas

Leases

, 71 SMU L. REV. 477 (2018)

https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol71/iss2/4

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted

for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit

http://digitalrepository.smu.edu.

T

HE

E

NFORCEABILITY OF

C

ONSENT

-

TO

-A

SSIGN

P

ROVISIONS IN

T

EXAS

O

IL AND

G

AS

L

EASES

T. Ray Guy & Jason E. Wright*

ABSTRACT

Oil and gas leases are unique instruments that, on their face, appear to be

contracts or traditional landlord–tenant leases. Indeed, landowners often

desire to have them treated as such by including provisions giving a lessor

power to limit or control any assignment of the lease. Typically, this takes

the form of a consent-to-assign provision seen in many types of ordinary

contracts and leases. In Texas, however, an oil gas lease actually conveys a

fee simple property interest; and property law, far more than contract or

landlord–tenant law, greatly disfavors any restraint that acts to restrict the

free transferability (or “alienation”) of property rights. As such, an inher-

ent tension may exist between a lessor who has a right to withhold consent

to an assignment under the lease terms and a lessee who desires to transfer

the drilling rights to others.

Nonetheless, Texas courts have rarely had occasion to pass on the en-

forceability of consent-to-assign provisions in the oil and gas leasing con-

text, primarily because commercial parties generally are more apt to be

reasonably and reach agreements when times are good. The prolonged

downturn in oil prices, however, is likely to result in increased litigation in

many areas. There is a potential, in particular, that lessors may seek to

exploit the lack of developed case law in the consent-to-assign area by de-

manding “consent fees” or attempting to terminate leases if assigned with-

out consent. This article thus analyzes the legal underpinnings in Texas to

provide guidance to lessees faced with unreasonable demands or litigation

risk and concludes that, in most situations, a consent-to-assign provision is

not as enforceable as it may appear, while further suggesting practical ways

in which to mitigate the risks of routine assignment.

* The authors are attorneys in the Dallas office of Weil, Gotshal & Manges LLP, and

would like to thank their colleague Rodney L. Moore for assistance in reviewing and im-

proving this article.

477

478 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 479

II. OIL AND GAS LEASES IN TEXAS ARE PRIMARILY

FEE SIMPLE PROPERTY INTERESTS ................. 480

III. A LIMITATION ON THE ABILITY TO ASSIGN AN

OIL AND GAS LEASE IN TEXAS IS A RESTRAINT

AGAINST ALIENATION ................................ 483

A. P

ROMISSORY

R

ESTRAINTS

............................. 485

B. D

ISABLING

R

ESTRAINTS

............................... 491

C. F

ORFEITURE

R

ESTRAINTS

............................. 492

D. D

EFENSES TO

V

IOLATION OF A

V

ALID

R

ESTRAINT

.... 495

IV. APPLICATION TO COMMON CONSENT

PROVISIONS ............................................ 496

A. O

VERVIEW

............................................ 496

B. A

NALYSIS OF

S

PECIFIC

C

LAUSES

...................... 498

1. “This lease shall not be assigned.” ................. 498

2. “This lease shall not be assigned without lessor

consent.” .......................................... 498

3. “This lease shall not be assigned without lessor

consent, such consent not to be unreasonably

withheld.” ......................................... 499

4. “Any attempt or offer to assign shall be . . . .” ..... 500

5. “Any assignment made without prior written

consent of lessor shall be void.” ................... 501

6. “Any assignment made without prior written

consent of lessor shall result in a forfeiture of all

rights granted hereunder.” ......................... 501

7. “This lease shall not be assigned to XYZ Drilling

Company without lessor’s written consent. Any

assignment made to XYZ Drilling Company

without prior written consent of lessor shall result in

all rights reverting back to lessor.” ................. 502

V. POTENTIAL ALTERNATIVE FORMS OF

ACCOMPLISHING A TRANSFER ...................... 502

VI. CONCLUSION ........................................... 504

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 479

I. INTRODUCTION

C

ONTRACT law and property law both serve several important

goals in a free-market society. Perhaps the most evident aim of

contract law is to provide assurance that promises will be en-

forced (through expectancy damages at the least). Property law seeks

similar predictability but at the same time strives to promote a “better

utilization of society’s wealth by . . . assisting in assets flowing to those

who would put them to their best use.”

1

On occasion those objectives

may conflict. This article explores the outcome of such a conflict in the

context of Texas oil and gas leases that contain provisions that purport to

give a landowner power to restrict the assignment of the leased rights to

others.

The upstream oil and gas business achieves efficiency in large part

based upon the ability to buy, sell, or otherwise transfer drilling rights

obtained by lease, and in practice, it is routine for those rights to change

hands several times before a single well is ever drilled. There are several

practical reasons why that may occur: (i) the landman who first signs up a

property owner may be a speculator with no intent of developing the

rights; (ii) the circumstances for the original lessee may change such that

it becomes unable to drill; or (iii) a producer may need to prioritize and

redirect its resources to other assets. In general, then, the free transfera-

bility of oil and gas leases maximizes profit-making opportunities for both

landowners and producers by naturally guiding drilling rights into the

hands of those most likely to use them.

Nevertheless, some landowners seek to limit the assignability of a

lease—most often to maintain control over who works on their land and

to ensure the leasing counterparty is financially responsible enough to be

held accountable for any problems that may arise (such as excessive sur-

face damage or underpayment of royalties).

2

It would be unusual for a

landowner to seek to prohibit assignment altogether—or for one to have

the negotiating power to attain such a concession—yet it is fairly common

for oil and gas leases in Texas to contain a clause requiring lessor consent

prior to an assignment. Most often such consent right is coupled with the

corresponding obligation that consent “shall not be unreasonably with-

held,” but on occasion there are provisions that go further to declare that

any assignment done without consent is void or that the entire lease ter-

minates as a penalty. When parties fail to act rationally, such provisions

can end up straddling the fault line between enforcing contractual

promises and encouraging the most beneficial use of real property

interests.

1. Procter v. Foxmeyer Drug Co., 884 S.W.2d 853, 862 (Tex. App.—Dallas 1994, no

writ).

2. See Luke Meier & Rory Ryan, The Validity of Restraints on Alienation in an Oil

and Gas Lease, 64 B

UFF

. L. R

EV

. 305, 317 (2016) (describing what the authors termed a

“partnership” between landowner and extractor).

480 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

Given the current downturn in oil markets and expectation that prices

will remain far less than $100 per barrel for the foreseeable future, it is

conceivable that some lessors may seek to offset lower returns by way of

litigation. Consent-to-assign provisions are one area subject to potential

exploitation due to the lack of developed case law in Texas that addresses

the enforceability (or unenforceability) of such clauses in an oil and gas

leasing context. Lessors may attempt to use that uncertainty to demand

excessive “consent fees” or free themselves entirely to sign new leases on

better terms.

3

Past legal scholarship has touched on the enforceability of

consent-to-assign provisions, but it focuses more on guidelines for draft-

ing or has become dated given updates to the authoritative sources.

4

This

article thus surveys the current state of the law in Texas to provide lessees

with some guidance in managing the risks of routine assignment, which

may occur in bulk during a merger, acquisition, or restructuring.

In short, although Texas courts have rarely addressed consent-to-assign

provisions in the context of an oil and gas lease, all indications are that,

except for limited types of forfeiture clauses that should be handled with

caution, the contractual right to withhold consent to an assignment will

most often yield to the objective of ensuring free alienability of property

rights (or have such a trivial impact as to be effectively inconsequential).

The following examines the legal underpinnings for that conclusion and

applies the current legal guidance available to various types of language

that may be found in a consent-to-assign provision, while further sug-

gesting ways to mitigate the impact of a lessor acting unreasonably to

prevent transfer.

II. OIL AND GAS LEASES IN TEXAS ARE PRIMARILY FEE

SIMPLE PROPERTY INTERESTS

A critical threshold step in evaluating any legal issue is to first deter-

mine the body of law that applies. Oil and gas leases have features that

impact both contract and property law, each of which deal with restric-

tions on the ability to transfer rights in sometimes divergent ways.

Texas, as with most jurisdictions, favors the free transferability of con-

3. Indeed, one case being petitioned for review by the Texas Supreme Court at the

time of drafting—Barrow-Shaver Res. Co. v. Carrizo Oil & Gas, Inc.—involves a lessee

who demanded $5 million to give its consent to a driller’s assignment of their farmout

agreement to another driller in what would have been a $27.69 million transaction. 516

S.W.3d 89 (Tex. App.—Tyler 2017, pet. filed) (petition for review filed June 7, 2017, No.

17-0332).

4. See, e.g., Benjamin Robertson, Katy Pier Moore & Corey F. Wehmeyer, Consent

to Assignment Provisions in Texas Oil and Gas Leases: Drafting Solutions to Negotiation

Impasse, 48 T

EX

. T

ECH

L. R

EV

. 335 (2016); Terry I. Cross, The Ties That Bind: Preemptive

Rights and Restraints on Alienation that Commonly Burden Oil and Gas Properties, 5 T

EX

.

W

ESLEYAN

L. R

EV

. 193 (1999); David E. Pierce, An Analytical Approach to Drafting As-

signments, 44 S

W

. L.J. 943 (1990); see also Meier & Ryan, supra note 2, at 308 (advocating

for courts to enforce consent-to-assign provisions in oil and gas leases on a commercial

transaction basis alone).

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 481

tract rights

5

while also allowing parties the freedom to agree otherwise

(so long as their agreement is not contrary to public policy).

6

A basic

tenet of property law as well is the power to “alienate” property.

7

A

traditional lease of real property crosses over the two realms such that it

results in a rather distinct body of law: landlord–tenant law. Traditionally,

landlord–tenant law allows a number of restrictions to be placed on a

lessee, and in fact, the statutory default in Texas is that landlord consent

is required before surface property leased for commercial or residential

purposes (such as an apartment or farming acreage) may be sublet to a

third party.

8

An oil and gas lease, however, is quite different from an ordinary

rental arrangement. It necessarily involves interference with the surface

land that still belongs to, and is often concurrently occupied and used by,

the lessor, along with removal of physical property that exists below the

surface (i.e., the minerals). That unique nature has resulted in differing

viewpoints nationwide as to how to categorize an oil and gas lease. Sev-

eral states view an oil and gas lease as granting no more than an exclusive

right to profit on the minerals once they have been extracted from the

ground (a “profit `a prendre”),

9

others treat it as creating a fee simple

5. See In re FH Partners, L.L.C., 335 S.W.3d 752, 761 (Tex. App.—Austin 2011, no

pet.) (“Although the Agreement contains no terms that explicitly either authorize or pro-

hibit assignment, the presumption or general rule under Texas law, as FH emphasizes, is

that all contracts are freely assignable.”) (citing Crim Truck & Tractor Co. v. Navistar Int’l

Transp. Co., 823 S.W.2d 591, 596 (Tex. 1992) and Dittman v. Model Baking Co., 271 S.W.

75, 77 (Tex. Comm’n App. 1925, judgm’t adopted)).

6. See Pagosa Oil & Gas, L.L.C. v. Marrs & Smith P’ship, 323 S.W.3d 203, 211 (Tex.

App.—El Paso 2010, pet. denied) (stating that anti-assignment clause in a contract “[is]

enforceable in Texas unless rendered ineffective by a statute”); see also Sonny Arnold, Inc.

v. Sentry Sav. Ass’n, 633 S.W.2d 811, 815 (Tex. 1982) (noting parties have a “right to con-

tract with regard to their property as they see fit, so long as the contract does not offend

public policy and is not illegal”).

7. See Carder v. McDermett, 12 Tex. 546, 549 (1854) (“It will be admitted as a princi-

ple not to be questioned, that the power to alienate property is a necessary consequence of

ownership, and is founded on natural right.”).

8. See T

EX

. P

ROP

. C

ODE

A

NN

. § 91.005 (West 2016).

9. See, e.g., SEMO, Inc. v. Bd. of Comm’rs, 993 So. 2d 222, 226 (La. App. 1st Cir.

2008) (“Under Louisiana law, the ownership of land does not include ownership of oil, gas,

and other minerals occurring naturally in liquid or gaseous form. Rather, the landowner

has the exclusive right to explore and develop his property for the production of such

minerals and to reduce them to possession and ownership.”); State v. Pennzoil Co., 752

P.2d 975, 980 (Wyo. 1988) (“In Wyoming, the right created by an oil and gas lease is a

profit ´a prendre, connoting the right ‘to search for oil and gas and if either is found, to

remove it from the land.’”) (citations omitted); Shearer v. United Carbon Co., 103 S.E.2d

883, 886 (W. Va. 1958) (“The interest which a lessee secures by an oil and gas lease under

the later decisions of this Court is an inchoate and contingent interest. It creates in the

lessee a vested right to produce the minerals pursuant to the terms of the lease after dis-

covery thereof.”); Gavina v. Smith, 154 P.2d 681, 683 (Cal. 1944) (“It is settled in this state

that an oil lease like the one in the present case creates a profit `a prendre and vests in the

lessee an estate in real property . . . and that the owner may not quiet his title against such

a vested interest.”) (citations omitted); see also In re Aurora Oil & Gas Corp., 439 B.R.

674, 678–79 (Bankr. W.D. Mich. 2010) (noting court persuaded “that Michigan treats a

lessee’s interest as a leasehold or profit `a prendre, but not a freehold estate.”); see R

E-

STATEMENT

(T

HIRD

)

OF

P

ROP

.: S

ERVITUDES

§ 1.2 (2000) (“A profit `a prendre is an ease-

482 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

property interest in the minerals themselves,

10

and a few regard such a

lease as creating a hybrid in between those two main viewpoints.

11

Thus,

landlord–tenant principles may or may not be significant depending on

how the jurisdiction at issue characterizes the legal rights created by an

oil and gas lease.

12

In Texas, it is well established that an oil and gas lease is a “lease” in

name only and that landlord–tenant law has no application. Despite the

contractual form and name of the instrument, it actually conveys a fee

simple determinable

13

interest in the minerals themselves. The Texas Su-

preme Court succinctly summarized that position in the 2003 case of Nat-

ural Gas Pipeline Company of America v. Pool:

[I]t has long been recognized that an oil and gas lease is not a “lease”

in the traditional sense of a lease of the surface of real property. In a

typical oil or gas lease, the lessor is a grantor and grants a fee simple

determinable interest to the lessee, who is actually a grantee. Conse-

quently, the lessee/grantee acquires ownership of all the minerals in

place that the lessor/grantor owned and purported to lease, subject

to the possibility of reverter in the lessor/grantor. The lessee’s/

grantee’s interest is “determinable” because it may terminate and re-

vert entirely to the lessor/grantor upon the occurrence of events that

ment that confers the right to enter and remove timber, minerals, oil, gas, game, or other

substances from land in the possession of another.”).

10. See, e.g., Maralex Res., Inc., v. Chamberlain, 320 P.3d 399, 403 (Colo. App. 2014)

(“The Colorado Supreme Court has also recognized that ‘the majority rule in western

states appears to favor interpretation of the lessee’s interest in the oil and gas lease as an

interest in real estate.’ . . . Accordingly, as implicitly accepted in Hagood, we conclude that

an oil and gas lessee has an interest in real property.”) (citations omitted); T.W. Phillips

Gas & Oil Co. v. Jedlicka, 42 A.3d 261, 267 (Pa. 2012) (“If development during the agreed

upon primary term is unsuccessful, no estate vests in the lessee. If, however, oil or gas is

produced, a fee simple determinable is created in the lessee, and the lessee’s right to ex-

tract the oil or gas becomes vested.”); Jupiter Oil Co. v. Snow, 819 S.W.2d 466, 468 (Tex.

1991) (“The common oil and gas lease is a fee simple determinable estate in the realty.”);

Shields v. Moffitt, 683 P.2d 530, 532–33 (Okla. 1984) (“From the foregoing, we conclude

that the holder of an oil and gas lease during the primary term or as extended by produc-

tion has a base or qualified fee, i.e., an estate in real property having the nature of a fee,

but not a fee simple absolute.”); Rock Island Oil & Refining Co. v. Simmons, 386 P.2d 239,

241 (N.M. 1963) (“It is well settled in New Mexico that an oil and gas lease conveys an

interest in real estate.”); see also Maralex Res., Inc. v. Gilbreath, 76 P.3d 626, 630 (N.M.

2003) (“The typical oil and gas lease grants the lessee a fee simple determinable interest in

the subsurface minerals within a designated area.”).

11. See, e.g., Ingram v. Ingram, 521 P.2d 254, 258 (Kan. 1974) (“It is obvious from this

analysis of the Kansas statutes and decisions that in this state an oil and gas lease is a

hybrid property interest. For some purposes an oil and gas leasehold interest is considered

to be personal property and for other purposes it is treated as real property.”).

12. See, e.g., Harding v. Viking Int’l Res. Co., Inc., 1 N.E.3d 872, 875 (Ohio App. 2013)

(construing Ohio law to view an oil and gas lease as simply a contract and, as such, voiding

an assignment made without consent).

13. The event that makes the fee simple interest “determinable” is when the land stops

producing oil and gas in paying quantities. See Krabbe v. Anadarko Petroleum Corp., 46

S.W.3d 308, 315 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 2001, pet. denied) (“The language of a typical oil or

gas lease is such that the lease may be kept alive after the primary term only by production

in paying quantities or a savings clause, such as a shut-in royalty clause, continuous opera-

tions clause, drilling operations clause, etc.”).

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 483

the lease specifies will cause termination of the estate.

14

Moreover, an oil and gas lease creates a fee simple determinable in Texas

regardless of the granting terms used or contrary efforts of the parties.

15

As a result, an oil and gas lease of Texas land that is silent regarding

assignability is freely transferable according to the general rule that all

real property interests (and contract rights) are assignable.

16

If the parties

agree otherwise by including terms in the lease placing restrictions on

assignment, then standard contract interpretation rules apply to construe

the language in the context of the common law governing conveyances of

estates in fee simple,

17

which may result in some surprising outcomes.

III. A LIMITATION ON THE ABILITY TO ASSIGN AN OIL

AND GAS LEASE IN TEXAS IS A RESTRAINT

AGAINST ALIENATION

It has long been true in Texas that any limitations placed on a person’s

right to sell or dispose of real property interests granted in fee simple

terms are “restraints upon alienation” that are greatly disfavored as a

14. 124 S.W.3d 188, 192 (Tex. 2003).

15. See Stephens County v. Mid-Kansas Oil & Gas Co., 254 S.W. 290, 294 (Tex. 1923)

(“Notwithstanding the distinctions attempted to be drawn in the decisions, we cannot con-

clude otherwise than that there is no real difference in the title conveyed, whether an

instrument takes the form of a grant of the exclusive right to mine and appropriate all of a

certain mineral (as in Benevides v. Hunt, supra), or takes the form of a demise of the land,

for the sole purpose of mining operations, coupled with a grant of the exclusive right to

produce and dispose of the mineral (as in this case), or takes the form of a grant of the

mineral with the exclusive right to mine for, produce, and dispose thereof (as in Texas Co.

v. Daugherty, supra). The results are substantially the same to all parties at interest,

whether the one or other form of instrument be used. Why hold that instruments in differ-

ent forms create different estates, where there is no difference in fact with respect to that

of which each divests the grantor, his heirs or assigns, nor with respect to that with which

each invests the grantee, his heirs or assigns?”).

16. See, e.g., Phillips v. Oil, Inc., 104 S.W.2d 576, 579 (Tex. Civ. App.—Eastland 1937,

writ ref’d) (“There is nothing in either of said four [oil and gas leases] prohibiting its as-

signment. Under such situation, there is nothing to prevent the application of the general

rule and the Texas statute providing for the assignability of all written contracts . . . .”);

Watts v. England, 269 S.W. 585, 587–88 (Ark. 1925) (“The lease in question contained no

covenant against assigning it, and could therefore be assigned to J. E. England, Jr., trus-

tee.”); 4 E

UGENE

K

UNTZ

, A T

REATISE ON THE

L

AW O F

O

IL AND

G

AS

§ 51.2(a) (1990)

(“There is no reason to doubt that the lessee may freely assign the lease, in whole or in

part, with or without such a clause [allowing assignment].”).

17. Although an oil and gas lease is not a fee simple absolute since it will eventually

terminate (making it a fee simple determinable), the First Restatement directs that “defea-

sible” estates should be analyzed under the same rules applicable to “indefeasible” estates

if they are otherwise “readily marketable.” R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 407 cmt. b

(1944). In general, oil and gas interests are so highly marketable that they would likely be

treated the same as a fee simple absolute in any suit implicating a consent-to-assign

provision.

484 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

matter of public policy.

18

,

19

Due to the strong bias against such restraints,

any conveyance of property rights—including those in an oil and gas

lease—that purport to restrict the ability to transfer the rights to others is

“strictly construed.”

20

That means the language is interpreted according

to its precise, literal meaning. For example, a provision restricting the as-

signment of a lease is unlikely to be construed so as to prevent other

dispositions, such as a sublease of less than the entire interest.

21

No court

18. See Robbins v. HNG Oil Co., 878 S.W.2d 351, 363 (Tex. App.—Beaumont 1994,

writ dism’d w.o.j.) (“But it is Hornbook law and an axiomatic rule that restraints on aliena-

tion are squarely contrary to public policy and are forbidden and disallowed.”); see also

O’Connor v. Thetford, 174 S.W. 680, 681 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio 1915, writ ref’d)

(“The tying up of property was regarded by the common law as an evil, and in order to

prevent it two doctrines were established, one that all interests should be alienable, the

other that all interests must arise within certain limits, the latter being known as the rule

against perpetuities. In this case we are concerned only with the first doctrine, and the

extent to which it exists in this state under the common law which has furnished our rules

for construing deeds since its adoption in 1840. It is well settled that a general restraint

upon the power of alienation when incorporated in a deed or will otherwise conveying a

fee-simple title is void . . . .”); Hicks v. Castille, 313 S.W.3d 874, 882 (Tex. App.—Amarillo

2010, pet. denied) (“The right of alienation is an inherent and inseparable quality of an

estate in fee simple.”) (citing Potter v. Couch, 141 U.S. 296, 315 (1890) (“A restriction . . .

not forbidding alienation to particular persons or for particular purposes only, but against

any and all alienation whatever during a limited time, of an estate in fee, is likewise void, as

repugnant to the estate devised to the first taker, by depriving him during that time of the

inherent power of alienation.”)); Griffin v. Griffin, No. 10-08-00327-CV, 2010 WL 140383,

at *4 (Tex. App.—Waco Jan. 13, 2010, pet. denied) (mem. op.) (noting the principle is

considered “well-settled in this state prior to 1909”) (citing Diamond v. Rotan, 124 S.W.

196, 198 (Tex. Civ. App.—Texarkana 1909, writ ref’d) (“That a general restraint upon the

power of alienation, when incorporated in a deed or will otherwise conveying a fee-simple

right to the property is void, is now too well settled to require discussion.”)).

19. The Dallas Court of Appeals in Procter v. Foxmeyer Drug Company identified the

public policy prohibiting restraints on alienation as serving at least three purposes:

1. Balanc[ing] the current property owner’s desire to prolong control over

his property and a latter owner’s desire to be free from the “dead” hand;

2. Contribut[ing] to better utilization of society’s wealth by reducing fear

from uncertain investments and assisting in assets flowing to those who

would put them to their best use; and

3. Keep[ing] the property available to satisfy the current exigencies of the

owner and, thus, stimulate the competitive theory basis of the economy.

884 S.W.2d 853, 862 (Tex. App.—Dallas 1994, no writ).

20. See Knight v. Chicago Corp., 188 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1945) (addressing oil and

gas lease, stating: “Since the petitioners are seeking to recover for a claimed violation of a

restriction against alienation, they must bring the act of their lessee strictly within the lan-

guage of the restriction.”); see also Clayton Williams Energy, Inc. v. BMT O & G TX, L.P.,

473 S.W.3d 341, 350 (Tex. App.—El Paso 2015, pet. denied) (strictly applying plain lan-

guage of assignment clause notwithstanding the claim that it would cause “absurd re-

sult[s]”); Crestview, Ltd. v. Foremost Ins. Co., 621 S.W.2d 816, 826 (Tex. Civ. App.—

Austin 1981, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (noting courts are instructed to “prefer a construction of a

possible restraint so that there is no such result”).

21. See, e.g., Amco Trust, Inc. v. Naylor, 317 S.W.2d 47, 50 (Tex. 1958) (“In order to

constitute an assignment, the lessee must part with his entire interest in all or part of the

demised premises without retaining any reversionary interest.”); 718 Assocs., Ltd. v. Sun-

west N.O.P., Inc., 1 S.W.3d 355, 360 (Tex. App.—Waco 1999, pet. denied) (discussing vari-

ous differences and effects between assignment and sublease); see also Jackson v. Sims, 201

F.2d 259, 262 (10th Cir. 1953) (finding prohibition against assignment of mineral lease on

Native American land in Oklahoma did not apply to sublease, stating: “The law generally

recognizes a distinction between an assignment and a sublease. Oklahoma follows the gen-

eral rule to the effect that a conveyance which does not pass the whole interest of the

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 485

in Texas appears to have specifically addressed the assignment–sublease

distinction for purposes of a consent-to-assign provision in an oil and gas

lease, but there are cases that use analogous reasoning to rule that an

anti-assignment clause in no way limits a lessee’s ability to assign a cause

of action related to the lease, as those are distinct matters.

22

Further, in

“strictly construing” lease language, at least one Texas court has invali-

dated a provision prohibiting a lessee from making an “offer” or an “at-

tempt” to assign an oil and gas lease because of the lack of certainty that

exists in trying to determine all the instances when a person may offer or

attempt to do something.

23

This indicates the bias against such restraints

is, indeed, very heavy in Texas.

Even if a limitation on assignment is clearly stated and directly applica-

ble, the preference to avoid a restriction on alienability requires that a

restraint be enforced only to the extent it is “reasonable.”

24

For guidance

in determining whether particular language constitutes an unreasonable

restraint, courts in Texas have consistently turned to the legal principles

summarized by the Restatements of Property.

25

The Restatement (First) of Property (the “First Restatement”) identi-

fies three categories of restraints against alienation—promissory re-

straints, disabling restraints, and forfeiture restraints

26

—each of which

are discussed in more detail in the following sections. In general, how-

ever, disabling restraints are always invalid as a matter of law,

27

and the

other two are enforceable if limited in specific ways to protect important

interests of the conveying party.

A. P

ROMISSORY

R

ESTRAINTS

Section 404(1)(b) of the First Restatement defines a promissory re-

straint as an attempt to “cause a later conveyance . . . to impose contrac-

lessee for the full term, but retains some sort of reversionary interest, is a sublease and not

an assignment.”).

22. See Pagosa Oil & Gas, L.L.C. v. Marrs & Smith P’ship, 323 S.W.3d 203, 211–12

(Tex. App.—El Paso 2010, pet. denied) (“Texas law recognizes a distinction between a

contracting party’s ability to assign rights under a contract containing an anti-assignment

provision, and that same party’s ability to assign a cause of action arising from breach of

that contract.”) (citing cases in support).

23. Knight v. Chicago Corp., 183 S.W.2d 666, 671 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio

1944), aff’d, 188 S.W.2d 564 (Tex. 1945) (“Conditions against alienation are strictly con-

strued, and even if they would otherwise be valid are ineffectual unless certainly and

clearly expressed. A provision restraining the grantee from ‘offering’ or ‘attempting’ to

alien[ate] is ordinarily void for uncertainty and cannot be restrained.”).

24. See Sonny Arnold, Inc. v. Sentry Sav. Ass’n, 633 S.W.2d 811, 819 (Tex. 1982)

(Spears, J., concurring) (“The mere fact that a contractual provision may restrain the alien-

ation of property does not mean that the provision is per se invalid. It is only unreasonable

restraints upon alienation which are not enforced.”).

25. See id. at 813 (majority opinion); see also Navasota Res., L.P. v. First Source Texas,

Inc., 249 S.W.3d 526, 537 (Tex. App.—Waco 2008, pet. denied) (noting Texas courts look to

Restatements and citing cases).

26. R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. §§ 404, 407 (1944).

27. Mattern v. Herzog, 367 S.W.2d 312, 319 (Tex. 1963) (noting rule that disabling

restraints are invalid); see also Deviney v. NationsBank, 993 S.W.2d 443, 449 (Tex. App.—

Waco 1999, pet. denied) (same).

486 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

tual liability on the one who makes the later conveyance when such

liability results from a breach of an agreement not to convey.”

28

The com-

ments to Section 404 include specific examples and note that such liability

results “not only when the promise not to convey is unqualified but also

when it is qualified by permitting alienation with consent and the consent

is not obtained.”

29

As a result, most basic consent-to-assign provisions in

an oil and gas lease will be promissory restraints, unless they contain ad-

ditional language that makes them fall into one of the other two catego-

ries (disabling restraints or forfeiture restraints) that are discussed in the

sections further below.

Under Section 406 of the First Restatement, a promissory restraint is

valid when it is: (i)”qualified so as to permit alienation to some though

not all possible alienees” and (ii)”reasonable under the circumstances.”

30

An unqualified prohibition against all assignment plainly does not satisfy

the first element and, as such, would likely be viewed by a Texas court as

unenforceable no matter the motive for the restriction or how reasonable

a lessor’s concerns may have been at the time of granting.

31

This is true

regardless of the fact that contract law would otherwise allow parties to

agree to prohibit all transfers without qualification because, in a real

property context, it simply violates public policy to so severely hamper

alienation.

32

Therefore, language stating that a real property interest “shall not be

assigned” at all would likely be viewed by a Texas court as invalid as a

matter of law.

On the other hand, a restriction limiting assignment to those for whom

the consent of another has been obtained (typically, the lessor) is likely

“qualified” in a way that would satisfy the first element of Section 406.

33

28. R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 404(1)(b).

29. Id. § 404 cmt. g.

30. Id. § 406(b)–(c).

31. Id. § 406 cmt. d (“An unqualified restraint on what is or otherwise would be a legal

possessory indefeasible estate in fee simple is an attempt to prevent perpetually the aliena-

tion of the estate in fee simple to all persons and by all available methods . . . . The objec-

tives which one imposing such an extensive restraint on alienation could have in mind are

never regarded as sufficiently meritorious to outweigh the evils which such interference

with the power of alienation would cause.”).

32. See N. Point Patio Offices Venture v. United Ben. Life Ins. Co., 672 S.W.2d 35, 38

(Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 1984, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (“No one suggests any social or

economic value of the provision here in question except that of the parties being able to

contract as they see fit. This is admittedly an important right, but its unfettered application

under these circumstances would effectively destroy the rule prohibiting unreasonable re-

straints on alienation of property.”); Crestview, Ltd. v. Foremost Ins. Co., 621 S.W.2d 816,

823 (Tex. Civ. App.—Austin 1981, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (“The matter of whether the clause is

an unreasonable restraint on alienation involves not the intention of the parties to a con-

tract, or their justifiable expectations thereunder, but the ascertainment and implementa-

tion of the broad public policies which justify the common-law rule that prohibits such

restraints.”).

33. See, e.g., Crestview, 621 S.W.2d at 826–27 (“If the clause in issue did constitute a

restraint on alienation, we would nevertheless be required to enforce it in this case because

it is expressly qualified by the requirement of reasonable conduct on the part of the note-

holder, which implies that alienation is permitted to some though not all possible alien-

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 487

The validity of such a provision would then depend on whether it meets

the second requirement, i.e., that the restriction be “reasonable under the

circumstances.” In making that determination, the First Restatement of-

fers a number of nonexclusive factors for a court to consider as to what is

both reasonable and unreasonable, all of which are listed in the footnote

below.

34

Unfortunately, many of the factors on both sides of the ledger

could easily go either way in a typical oil and gas leasing scenario, such

that the factors themselves are largely not helpful to a court analyzing the

issue. In the absence of developed case law, the First Restatement factors

by themselves provide little guidance.

Fortunately, more clarity may be gained from newer editions and sup-

plements to the Restatement. The Restatement (Third) of Property: Ser-

vitudes (the “Third Restatement”) in particular—published in 2000—

provides pertinent factors to consider in determining what constitutes a

reasonable restraint.

35

Section 3.4 of the Third Restatement states that a

ees.”). But see Williams v. Williams, 73 S.W.3d 376, 380 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.]

2002, no pet.) (finding a restriction in a will that property not be sold without consent of

other grantees void as a “general restraint on the power of alienation”); Deviney v. Nation-

sBank, 993 S.W.2d 443, 451 (Tex. App.—Waco 1999, pet. denied) (“The second sentence of

the devise prohibits Nolan Taylor’s daughters from conveying their interests in the Farm

without the consent of the co-owners. This constitutes an invalid disabling restraint on the

alienation of their interests. . . . Accordingly, it is void.”).

34. “The following factors, when found to be present, tend to support the conclusion

that the restraint is reasonable: the one imposing the restraint has some interest in land

which he is seeking to protect by the enforcement of the restraint; the restraint is limited in

duration; the enforcement of the restraint accomplishes a worthwhile purpose; the type of

conveyances prohibited are ones not likely to be employed to any substantial degree by the

one restrained; the number of persons to whom alienation is prohibited is small . . . ; the

one upon whom the restraint is imposed is a charity. The following factors, when found to

be present, tend to support the conclusion that the restraint is unreasonable: the restraint is

capricious; the restraint is imposed for spite or malice; the one imposing the restraint has

no interest in land that is benefited by the enforcement of the restraint; the restraint is

unlimited in duration; the number of persons to whom alienation is prohibited is large . . . .

The factors listed above as tending to support a conclusion that the restraint is reasonable

and those listed as tending to the opposite conclusion are not exhaustive. Each case must

be thoroughly examined in the light of all the circumstances to determine whether the

objective sought to be accomplished by the restraint is worth attaining at the cost of inter-

fering with the freedom of alienation or to determine whether the particular interference

with alienability is so slight as not to be material.” R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 406

cmt. i (1944) (emphasis added).

35. The Third Restatement has been applied by at least one Texas court in an oil and

gas case (involving preferential rights) and, thus, would likely be used to assess the validity

of a promissory restraint in a consent-to-assign provision. See Navasota Res., L.P. v. First

Source Texas, Inc., 249 S.W.3d 526, 538 (Tex. App.—Waco 2008, pet. denied) (citing both

First and Third Restatements in addressing joint operating agreement). There may be argu-

ments that Navasota should not have used the Third Restatement since an introductory

section states that “covenants in leases” are not addressed to “the extent that special rules

and considerations apply” to such servitudes, see R

ESTATEMENT

(T

HIRD

)

OF

P

ROP

.: S

ERVI-

TUDES

§ 1.1(2)(a) (2000), and comment e explains further that “[l]andlord-tenant law, real-

property security law, oil and gas law, timber law, and the law governing extraction of

other minerals” are specialized areas that the Third Restatement was not intended to

cover. Id. at cmt. e (emphasis added). However, given the set of topics in which the qualifi-

cation appears, the statement seems to be directed towards those jurisdictions which char-

acterize an oil and gas lease as something other than a fee simple interest. As a result,

there is a significant likelihood that a court in Texas assessing a consent provision in an oil

and gas lease would rely on the Third Restatement for guidance.

488 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

prohibition against transferring a property interest without the consent of

another is valid only if it is reasonable as determined by “weighing the

utility of the restraint against the injurious consequences of enforcing the

restraint.”

36

The comments go on to elaborate that a consent requirement

is presumptively unreasonable “unless there is strong justification for the

prohibition, and, unless the consent can be withheld only for reasons di-

rectly related to the justification for the restraint.”

37

Importantly, the

comments note further that if the language allows consent to be withheld

“arbitrarily,” then the restriction can be reasonable “only if the person

withholding consent is obligated to supply a substitute purchaser for the

property.”

38

Very few (if any) consent-to-assign provisions include an ob-

ligation for the lessor to find a substitute purchaser. As such, a provision

in an oil and gas lease stating that an assignment may not be done with-

out lessor consent—without further spelling out that the consent shall not

be unreasonably withheld—would be presumptively invalid under Sec-

tion 3.4 of the Third Restatement.

39

Assuming a consent-to-assign provision in the form of a promissory

restraint is qualified such that consent may not be unreasonably withheld,

Section 3.4 would then require “weighing” the utility of the consent re-

quirement against its injurious consequences to determine if the provision

can be enforced.

40

The most obvious and relevant “justification” for a

consent requirement in an oil and gas lease is to protect the owner of the

surface estate from having to deal with a lessee that has insufficient assets

against which to recover should there be excessive surface damage or

other disputes. However, the potential injurious consequences are nu-

merous—including, as identified by the Third Restatement:

(i) ”impediments to the operation of a free market in land;” (ii) “limiting

the prospects for improvement, development, and redevelopment” of the

land; (iii) “demoralization costs associated with subordinating the desires

of current landowners to the desires of past owners;” (iv) “frustrating the

expectations that normally flow from land ownership;” and (v) placing

one party “in a position to take unfair advantage of another’s need or

desire to transfer property.”

41

This litany of injurious consequences

36. R

ESTATEMENT

(T

HIRD

)

OF

P

ROP

.: S

ERVITUDES

§ 3.4; see also id. at cmt. b (stating

that “prohibitions on transfer without the consent of another” fall within requirements of

Section 3.4 of the Third Restatement).

37. Id. § 3.4 cmt. d.

38. Id.

39. A recent decision from the Tyler Court of Appeals reached the opposite conclu-

sion regarding a consent-to-assign provision in a farmout agreement. See Carrizo Oil &

Gas, Inc. v. Barrow-Shaver Res. Co., 516 S.W.3d 89, 96–97 (Tex. App.—Tyler 2017, pet.

filed). However, a farmout agreement often deals only with the provision of services such

that contract law alone may apply. To the extent the farmout agreement in Carrizo in-

volved a transfer of real property interests (if any), it does not appear that the parties

briefed the impact of property law, nor did the court of appeals address any principles of

property law. See generally id. At the time of drafting, however, the Carrizo case was being

petitioned for review by the Texas Supreme Court. See supra note 3.

40. R

ESTATEMENT

(T

HIRD

)

OF

P

ROP

.: S

ERVITUDES

§ 3.4.

41. Id. § 3.4 cmt. c.

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 489

weighs against the likelihood that a promissory restraint in the form of a

consent-to-assign provision in a Texas oil and gas lease would be reasona-

ble in all but the most lopsided circumstances (e.g., when the contem-

plated transferee is clearly disreputable, reckless, or a thinly-capitalized

shell entity).

42

The last injurious consequence identified above—placing one party in a

position to take unfair advantage of another’s need or desire to transfer

the property interest—is probably the most significant as it is that most

likely to occur on a routine basis. Counterparties in many settings have

not hesitated to use consent provisions to extract fees or concessions that

were never part of the original bargain. In many jurisdictions, such coer-

cion is constrained by the inherent duty of good faith and fair dealing.

43

But no such general duty of good faith and fair dealing exists in Texas.

44

Nevertheless, the fact that an oil and gas lease in Texas is a real property

interest brings into play the Third Restatement’s requirement that, when

consent is withheld, it be done only “for reasons directly related to the

justification for the restraint.”

45

A lessor who withholds consent for the

purpose of extracting additional financial gain or other unbargained-for

concessions—even when dealing with an original lessee—may, by such

coercive efforts alone, place itself squarely within the Third Restate-

ment’s presumption of unreasonableness and thereby negate any possibil-

ity of having the consent right enforced for legitimate reasons.

46

Even if a Texas court were to find a basic consent-to-assign provision to

be a reasonable restriction and determine the landowner had a legitimate

basis upon which to object to a particular assignee (doing so without ex-

ploitation of the consent right), there may still be no effective restriction

against assignment because, as a promissory restraint (i.e., a covenant),

violation of the consent right would give rise only to a cause of action for

damages. Absent a liquidated damages clause,

47

proving any harm re-

sulted from the mere fact of an assignment would typically be difficult

42. See, e.g., Carrizo, 516 S.W.3d at 94, 100 (noting an expert witness in that case,

Professor Bruce Kramer, testified the custom in the oil and gas industry is that “consent

could not be withheld absent a reasonable concern about the potential assignee’s capabili-

ties” and further, in the concurrence, noting Mr. Kramer stated the practice is for consent

to be given absent “a concern regarding the financial status, technical expertise, or general

reputation of the proposed assignee.”).

43. See, e.g., Dalton v. Educ. Testing Serv., 663 N.E.2d 289, 291 (N.Y. 1995) (“Where

the contract contemplates the exercise of discretion, this pledge includes a promise not to

act arbitrarily or irrationally in exercising that discretion.”); see also R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

C

ONTRACTS

§ 151(c) (1932); 69 A

M

. J

UR

. P

ROOF OF

F

ACTS

3d 191 § 12 (2002).

44. See Subaru of Am., Inc. v. David McDavid Nissan, Inc., 84 S.W.3d 212, 225 (Tex.

2002) (duty of good faith and fair dealing not recognized except for when contract creates

or governs special relationship between parties).

45. R

ESTATEMENT

(T

HIRD

)

OF

P

ROP

.: S

ERVITUDES

§ 3.4 cmt. d.

46. See, e.g., N. Point Patio Offices Venture v. United Ben. Life Ins. Co., 672 S.W.2d

35, 38 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 1984, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (“Because there was no

specific provision for such a ‘waiver’ fee, its imposition by the lender was coercive and by

its nature a restraint on alienation of the property.”).

47. See Trafalgar House Oil & Gas Inc. v. De Hinojosa, 773 S.W.2d 797, 799 (Tex.

App.—San Antonio 1989, no writ) ($1000 liquidated damages in event of failing to give

notice of assignment was valid and enforceable).

490 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

because there is nothing inherently damaging by a simple change in the

identity of the lessee. The First Restatement thus highlights that a promis-

sory restraint is, in practice, often one in form alone:

The fact that a promissory restraint is held valid does not mean that

all conceivable contractual remedies are available to the person enti-

tled to enforce the restraint. Sometimes the only available remedy

may be one for damages, and that even may be only a remedy for

nominal damages. If this is true, of course, the promissory restraint

does not operate as a significant impediment to the alienation of the

property.

48

The few Texas courts addressing the violation of a promissory consent-

to-assign provision in a real property context have tended to conclude

just that: there is no resulting harm.

For example, in Palmer v. Liles, a 1984 case involving a contract that

apportioned oil and gas mineral interests between co-owners and re-

quired consent prior to assignment, the First District Court of Appeals in

Houston emphasized that “breach of a provision preventing assignment

without consent of the original party will support an action for damages

when the party has suffered damages as a result of the breach,”

49

and the

appellate court affirmed the trial court’s ruling that no damages were suf-

fered by the mere fact that the consent requirement had been violated.

Similarly, in Haskins v. First City National Bank of Lufkin (decided in

1985), the Beaumont Court of Appeals addressed a land conveyance

made by appellant (Haskins) to her son that reserved a life estate and

prohibited any sale of the son’s interest without Haskins’ approval.

50

The

son defaulted on loans secured against his remainder and the bank fore-

closed. Haskins brought suit against both her son and the bank seeking to

have the original conveyance set aside for violation of the consent re-

quirement. The court ruled that, because the consent provision did not

provide Haskins with a right of reentry for its violation, it was a covenant

and she thus had, at best, a cause of action for breach of contract against

her son.

51

Yet, since Haskin’s life estate had not been disturbed (she re-

mained living on the property while the bank held the remainder), there

were no recoverable damages.

As a result, it appears that a promissory restraint in a Texas oil and gas

lease providing that no assignment may occur without lessor consent is, in

effect, not much of a prohibition on assignment at all. It would most

likely subject the assignor to damages, which in many instances would be

nonexistent with a simple change in identity of the lessee.

48. R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 404 cmt. g (1944).

49. 677 S.W.2d 661, 665 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 1984, writ ref’d n.r.e.) (em-

phasis in original).

50. 698 S.W.2d 754, 755 (Tex. App.—Beaumont 1985, no writ).

51. Id. at 756.

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 491

B. D

ISABLING

R

ESTRAINTS

Among the three types of restraints against alienation, those labeled as

disabling restraints are perhaps the easiest to analyze since they are

deemed invalid in virtually all circumstances. A disabling restraint is de-

fined in the First Restatement as an attempt to “cause a later conveyance

. . . to be void.”

52

The term “void” is further defined to include any provi-

sion that seeks to make a conveyance “have none of the legal conse-

quences intended.”

53

Under Section 405 of the First Restatement, all disabling restraints (ex-

cept those “imposed on equitable interests under a trust”) are outright

deemed invalid. The comments explain that the reason is due to an inher-

ent form of estoppel:

All restraints on alienation run counter to the policy of freedom of

alienation so that to be upheld they must in some way be justified.

But disabling restraints have an additional objection to their validity

since to be effective they must enable the person restrained to deny

the validity of his own conveyance and also, unless the restraint is

only as to voluntary conveyances, to deny his creditors resort to the

property interests which he is enjoying. The result is the rule stated

in this Section.

54

The few Texas courts addressing consent provisions that purport to au-

tomatically void an assignment have reached the same conclusion as the

First Restatement: that the attempted nullification was invalid as a matter

of law because the lessee who made the assignment was estopped from

denying the assignment and the grantor itself had no reversionary interest

allowing it to reenter and enforce a penalty.

55

As a result, a consent-to-assign provision in a Texas oil and gas lease

that purports to automatically void any assignment would likely be ruled

invalid as a matter of law.

52. R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 404(1)(a).

53. Id. § 404 cmt. f.

54. Id. § 405 cmt. a (emphasis added).

55. See, e.g., Bouldin v. Miller, 28 S.W. 940, 942 (Tex. 1894) (“Then, since this unlim-

ited power of alienation is a necessary incident to such estate, and since there is no person

who can enforce the attempted limitation on the power to sell when there is no condition,

it follows that the words of limitation in the deed above are ineffectual in law, and the deed

must be construed as if they had not been written therein.”); see also Williams v. Williams,

73 S.W.3d 376, 380 (Tex. App.—Houston [1st Dist.] 2002, no pet.) (finding provision in will

and partition deed preventing siblings from conveying their portions of devise without the

consent of other siblings to be unenforceable and denying siblings’ request to void assign-

ment to a third party); Deviney v. NationsBank, 993 S.W.2d 443, 451 (Tex. App.—Waco

1999, pet. denied) (“The second sentence of the devise prohibits Nolan Taylor’s daughters

from conveying their interests in the Farm without the consent of the co-owners. This con-

stitutes an invalid disabling restraint on the alienation of their interests. . . . Accordingly, it

is void.”).

492 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

C. F

ORFEITURE

R

ESTRAINTS

Forfeitures are not favored by Texas law.

56

Nonetheless, a consent-to-

assign provision drafted in a way so as to constitute a forfeiture restraint

should be carefully analyzed because it could result in a loss of rights if

worded correctly.

The First Restatement defines a forfeiture restraint as any attempt to

“cause a later conveyance . . . to terminate or subject to termination all or

a part of the property interest conveyed.”

57

Such restraints are subject to

the same rules as promissory restraints—i.e., they must be qualified so as

to permit alienation to “some though not all possible alienees” and be

“reasonable under the circumstances”—with the additional condition

that the rule against perpetuities must be satisfied.

58

The Restatement (Second) of Property: Donative Transfers (the “Sec-

ond Restatement”) addresses forfeiture restraints in detail.

59

In Section

4.2(3) of the Second Restatement, it is stated that a forfeiture restraint

imposed on an interest in property is “valid if, and only if, under all the

circumstances of the case, the restraint is found to be reasonable.” The

provision goes on to list factors commonly supporting a finding that a

forfeiture is reasonable:

(a) The restraint is limited in duration;

(b) The restraint is limited to allow a substantial variety of types of

transfers to be employed;

(c) The restraint is limited as to the number of persons to whom

transfer is prohibited;

(d) The restraint is such that it tends to increase the value of the

property involved;

56. See, e.g., Decker v. Kirlicks, 216 S.W. 385, 386 (Tex. 1919) (“Forfeitures are harsh

and punitive in their operation. They are not favored by the law, and ought not to be. The

authority to forfeit a vested right or estate should not rest in provisions whose meaning is

uncertain and obscure. It should be found only in language which is plain and clear, whose

unequivocal character may render its exercise fair and rightful.”); see also Knight v. Chi-

cago Corp., 183 S.W.2d 666, 671 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio 1944), aff’d, 188 S.W.2d

564 (Tex. 1945) (“The law looks with disfavor upon forfeiture provisions.”).

57. R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 404(1)(c).

58. See id. § 406; see also R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

P

ROP

: D

ONATIVE

T

RANSFERS

§ 4.2(3) (1983) (“A forfeiture restraint imposed on an interest in property . . . is valid if,

and only if, under all the circumstances of the case, the restraint is found to be

reasonable.”).

59. It should be noted that a restraint is more likely to be found “reasonable” in the

context of a commercial transaction than a donative transaction. This is because a con-

tracting party voluntarily accepts the restraint whereas, in a donative transfer, the donor

unilaterally imposes the restraint. See Procter v. Foxmeyer Drug Co., 884 S.W.2d 853, 858

(Tex. App.—Dallas 1994, no writ) (finding provisions in Second Restatement focused on

donative transfers can conclusively determine the validity—but not the invalidity—of re-

straints in commercial transactions); see also Meier & Ryan, supra note 2, at 320–39. How-

ever, while the Second Restatement is primarily focused on donative transfers, Section

4.2(3) specifically notes it applies to any forfeiture restraint not governed by the other

subsections therein (which more specifically apply to donative transfers). In any case, the

considerations are very similar to those in Section 406 (cmt. i) of the First Restatement and

Section 3.4 of the Third Restatement, which would otherwise apply to determine whether a

restraint is “reasonable.”

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 493

(e) The restraint is imposed upon an interest that is not otherwise

readily marketable; or

(f) The restraint is imposed upon property that is not readily

marketable.

60

Virtually all the factors listed above would weigh against a forfeiture

restraint being found reasonable in the context of an oil and gas lease;

particularly since the interests being restrained—i.e., drilling rights—are

highly marketable and since most consent-to-assign provisions are not

limited to specific persons or companies. Failing to draft a forfeiture re-

straint so as to exclude those to whom a transfer is most likely to occur

(other drilling companies in this instance) thus would appear to make it

unenforceable under the Second Restatement.

61

There is only one case in Texas that addresses a forfeiture restraint in

the context of an oil and gas lease, but there was no application of the

rules discussed above because the language of the lease was strictly con-

strued in a way so as to not restrict the assignment (not to mention the

Second Restatement did not exist at the time). Knight v. Chicago Corpo-

ration is a 1944 case in which the San Antonio Court of Civil Appeals

considered a lease that stated no assignment could be done without writ-

ten consent of the lessor and that, further, any “attempt to assign” a por-

tion of the lease would cause it to “ipso facto terminate as to the interest

so assigned, as well as all of the remaining interest” owned by the

lessee.

62

After the lease was pooled without consent, the lessor brought

suit seeking a declaration that forfeiture had occurred. The court of civil

appeals affirmed the trial court’s denial of the requested declaration.

Strictly construing the language, the court of appeals ruled that the lease

did not specifically prohibit unitization and, furthermore, that language

barring an “offer[ ]” or “attempt[ ]” to assign was void for lack of cer-

tainty

63

because it is near impossible to determine when one begins to

“attempt” an assignment. The Texas Supreme Court affirmed on slightly

different grounds. After first confirming that the language of a restriction

against alienability must be strictly construed,

64

the Supreme Court read

the exclusionary language as actually permitting the unitization agree-

ment at issue.

65

Likewise, in Outlaw v. Bowen, a 1955 case involving joint owners of a

mineral deed (not an oil and gas lease), the Amarillo Court of Civil Ap-

peals refused to enforce a provision that stated no conveyance or assign-

ment of the interest could be made “except in whole and that any attempt

to convey or assign any portion less than the whole thereof . . . shall

operate to forfeit the entire royalty hereby conveyed to the grantor

60. R

ESTATEMENT

(S

ECOND

)

OF

P

ROP

: D

ONATIVE

T

RANSFERS

§ 4.2(3).

61. See id. § 4.2 ill. 4 & cmt. r.

62. 183 S.W.2d 666, 668 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio 1944), aff’d, 188 S.W.2d 564

(Tex. 1945).

63. Id. at 671.

64. Knight v. Chicago Corp., 188 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1945).

65. Id. at 567–68.

494 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

herein, and any such conveyance or a portion thereof shall be null and

void.”

66

The court ruled the restriction invalid because the language did

not provide for an enforceable penalty

67

while also citing to Bouldin v.

Miller and Knight v. Chicago Corporation. Those citations indicate the

court’s conclusion could have been based on either: (i) the fact that there

was no stated reversion of the mineral rights to the grantor or anyone else

(i.e., what was lacking in Bouldin)

68

,

69

or (ii) the forfeiture was suppos-

edly triggered by an “attempt” to assign (i.e., what was ruled invalid in

Knight).

70

Either way, Outlaw further demonstrates that Texas courts are

loath to approve of a forfeiture provision even in a non-donative com-

mercial transfer.

A consent requirement that contains language of forfeiture should

nonetheless be closely evaluated because, unlike a promissory restraint

giving rise to damages, the consequences of ignoring such a provision

could be a loss of the entire lease. Indeed, the Texas Supreme Court’s

opinion in Knight v. Chicago Corporation noted that exact possibility,

stating:

If the parties to the lease bound themselves by language which can

be given no other reasonable construction than one which works

such result [i.e., a forfeiture], it is the court’s duty to give effect

thereto by declaring a termination, but if there is any uncertainty in

the language so as to make it ambiguous or of doubtful meaning,

relief should be denied them.

71

66. 285 S.W.2d 280, 283 (Tex. Civ. App.—Amarillo 1955, writ ref’d n.r.e.).

67. Id.

68. See Bouldin v. Miller, 28 S.W. 940, 941–42 (Tex. 1894) (“Livery of seisin being

necessary to the creation of such estate, it could at common law be defeated only by corre-

sponding notoriety of re-entry. If, as above shown, the conveyance is good at all events

against the grantor therein, and good as to the original grantor until re-entry for condition

broken, even when there is a condition against alienation, then it results that the convey-

ance would be valid as to both of said grantors when there is no condition annexed to said

estate. The first grantor could not complain because there would be no condition broken,

and therefore no right of reentry in him; and the second grantor could not complain be-

cause he would be estopped by his own conveyance. Thus, it appears that unlimited power

of alienation exists in such cases, as stated above, no matter what conditions or limitations

are sought to be imposed, and that the common law afforded no remedy for breach or

violation of such conditions or limitation except the right of re-entry for condition broken;

and that only affected the right of the grantee in the prohibited conveyance. Then, since

this unlimited power of alienation is a necessary incident to such estate, and since there is

no person who can enforce the attempted limitation on the power to sell when there is no

condition, it follows that the words of limitation in the deed above are ineffectual in law,

and the deed must be construed as if they had not been written therein.”).

69. Outlaw also cited a case from the Kansas Supreme Court—Somers v. O’Brien—

that found the lack of a right of reentry, among other provisions, rendered restrictive lan-

guage ineffectual. See Somers v. O’Brien, 281 P. 888, 890 (Kan. 1929) (“And so here, the

parents granted the premises to Magdelina with many restrictive but ineffective words. In

Wright v. Jenks it was provided that, if the restrictions were breached, the estate conveyed

was to terminate in the grantee and pass over to his collateral kindred. In this case, if the

restrictions are breached, what happens? Nothing. There is neither to be a re-entry of the

grantors nor an alternative grant or other consequence.”).

70. See supra notes 23 and 63 and accompanying text.

71. 188 S.W.2d 564, 566 (Tex. 1945).

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 495

It is not clear if the above-quoted dicta would be followed by the Texas

Supreme Court today as there are no subsequent cases involving a lessor

seeking to terminate an oil and gas lease due to a lessee’s failure to obtain

consent, and the Second Restatement did not exist at the time of the

opinion in 1944 (it was first published in 1983). Nevertheless, a prudent

lessee should take the time to identify and carefully analyze any forfei-

ture provisions based on the mere possibility of termination alone.

D. D

EFENSES TO

V

IOLATION OF A

V

ALID

R

ESTRAINT

Waiver, estoppel, and related defenses (such as laches) are additional

factors to consider when evaluating the enforceability of a consent-to-

assign provision in a Texas oil and gas lease. At least one appellate court

in Texas has highlighted that the nature of a consent requirement itself is

such that a forfeiture could never truly be “automatic,” even if properly

worded, and instead would always require a suit or other action by the

aggrieved party to perfect a forfeiture.

72

Therefore, given the strong bias

in Texas against restraints on alienation and forfeitures, any action taken

by a lessor after assignment has occurred that is contrary to the consent

right makes the lessor highly vulnerable to waiver and estoppel doctrines.

Section 421 of the First Restatement expressly notes that the issue of

waiver in the context of a restraint against alienation is given a “wider

meaning” than for contracts generally,

73

and it states that a waiver may

thus result if the holder of a consent right accepts any payment from the

new owner of the lease or if there is a “long continuing failure to take

action after the violation of the restraint becomes known.”

74

Ordinarily it

would make sense then to always give notice of an assignment to a lessor

regardless of whether consent was sought and rebuffed or the lessee de-

cided to move forward without seeking consent in the first place. The

failure of a lessor to immediately act after being given notice of a transfer

makes them susceptible to waiver.

Section 422 of the First Restatement similarly provides that any con-

duct which induces reliance on a mere “inference” that the lessee does

not intend to exercise its consent right can result in estoppel. That could

potentially occur whenever: (i) a lessee obtained some type of genera-

lized advance consent; (ii) the lease was previously assigned without con-

sent but the landowner did not complain; or (iii) the landowner has

received notice of an assignment (in any way) and the new owner of the

lease begins taking actions—such as commencement of drilling opera-

tions—while the landowner sits on its hands and does not immediately

72. See Knight v. Chicago Corp., 183 S.W.2d 666, 671 (Tex. Civ. App.—San Antonio

1944) (“Under the contract, therefore, the validity of an assignment of an undivided inter-

est rests with the option of the lessors. The clause therefore possesses the characteristics of

a condition subsequent rather than those of a limitation. In our opinion an optional re-

straint upon alienation of the nature here involved can not operate by way of limitation.”),

aff’d 188 S.W.2d 564 (Tex. 1945).

73. R

ESTATEMENT

(F

IRST

)

OF

P

ROP

. § 421 cmt. a (1944).

74. Id. § 421 cmt. c.

496 SMU LAW REVIEW [Vol. 71

act to enforce the consent right.

75

In fact, in Knight v. Chicago Corpora-

tion again, the San Antonio Court of Civil Appeals noted as alternative

support for its ruling that it could have found a waiver occurred by em-

phasizing the lessors treated the lease as valid by accepting royalties and

“procuring the drilling of an offset well” after they knew of the “attempt

to assign.”

76

In the appellate court’s opinion, such conduct meant the les-

sors waived any right to later insist on forfeiture (if forfeiture had been a

valid remedy to begin with). Courts in other jurisdictions have ruled

similarly.

77

As a result, the defenses of waiver, estoppel, and laches—all largely

based on simple notice to the lessor that an assignment will or has oc-

curred despite the lack of consent—should be taken into account as part

of any mitigation strategy.

IV. APPLICATION TO COMMON CONSENT PROVISIONS

A. O

VERVIEW

Language providing that a fee simple determinable interest—such as

that created by an oil and gas lease in Texas—cannot be transferred with-

out the consent of another may constitute any one of the three types of

restraints on alienation depending on how the provision is worded and

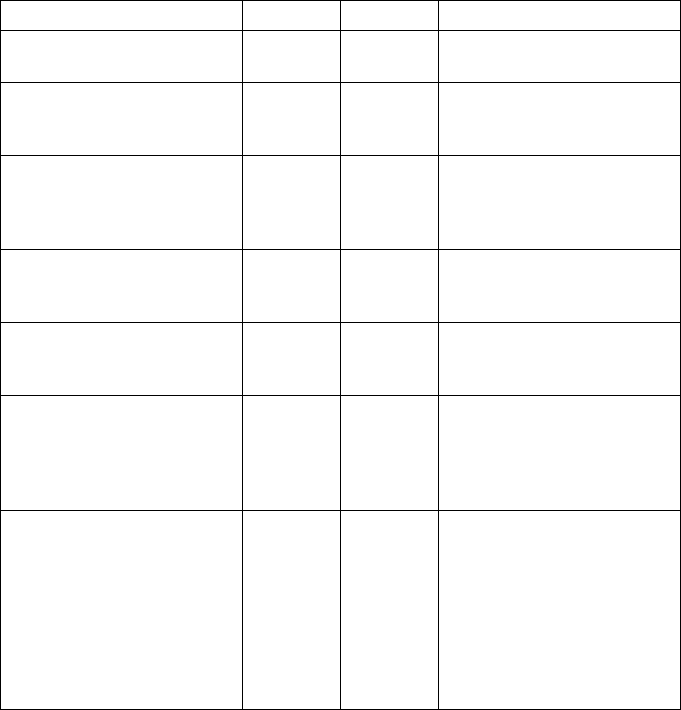

the remedies it provides. The following chart identifies and categorizes

the most common language likely to be encountered:

75. Id. § 422 cmt. b.

76. 183 S.W.2d at 672.

77. See, e.g., Prairie Oil Co. v. Carleton, 205 P.2d 81, 84 (Cal. App. 4th Dist. 1949)

(“The acceptance of rents by the landlord after breach of the conditions of an oil lease,

with full knowledge of all the facts, is a waiver of the breach and precludes the landlord

from declaring a forfeiture of the lease by reason of the breach.”); Scott v. Signal Oil Co.,

128 P. 694, 695 (Okla. 1912) (“It seems to us that the conduct of the lessor was so inconsis-

tent with a purpose to stand upon her rights under the assignment clause of the lease that

there is no room for a reasonable inference to the contrary.”). But see Stanolind Oil & Gas

Co. v. Guertzgen, 100 F.2d 299, 300–02 (9th Cir. 1938) (ruling Montana law favored the

forfeiture of oil and gas leases and that acceptance of three small royalty checks for

amounts past due after notice of assignment was not a waiver because the new owner of

the lease had not changed its position in reliance on lessor’s conduct).

2018] Enforceability of Consent-to-Assign 497

Type Effect Basis

Example Language

“This lease shall not be

Promissory Invalid 1st Rest. § 406(b) & cmt. d

assigned.”

“This lease shall not be

Likely

assigned without lessor con- Promissory 3d Rest. § 3.4 cmt. d

Invalid

sent.”

“This lease shall not be

Likely

assigned without lessor con- 1st Rest. § 404 cmt. g;

Promissory Valid:

sent, such consent not to be Palmer v. Liles (Tex. App.)

Damages

unreasonably withheld.”

Knight v. Chicago (Tex.

“Any attempt or offer to

— Invalid App.);

assign shall . . . .”

Outlaw v. Bowen (Tex. App.)

“Any assignment made with-

1st Res. § 405 & cmt. a;

out prior written consent of Disabling Invalid

Bouldin v. Miller (Tex. S. Ct.)

lessor shall be void.”

“Any assignment made with-

out prior written consent of

2d Rest. § 4.2(3);

lessor shall result in a forfei- Forfeiture Invalid

Outlaw v. Bowen (Tex. App.)

ture of all rights granted here-

under.”

“This lease shall not be

assigned to XYZ Drilling

Company without lessor’s

Specific

written consent. Any assign- Likely 2d Rest. § 4.2(3);

Forfeiture

ment made to XYZ Drilling Valid: Knight v. Chicago (Tex. S.

w/

Company without prior writ- Forfeiture Ct.)

Reversion

ten consent of lessor shall

result in all rights reverting