13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

THE EFFICIENT MERGER: WHEN AND WHY COURTS INTERPRET

BUSINESS TRANSACTIONS TO TRIGGER ANTI-ASSIGNMENT AND ANTI-

TRANSFER PROVISIONS

Philip M. Haines

*

I. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................684

II. TWO DISTINCT INTERPERTATIONS: DECIPHERING THE TXO

AND PPG LINES OF CASES ......................................................687

A. The TXO Line: Why Have Texas Courts Historically

Interpreted Anti-Assignment and Anti-Transfer

Provisions As Being Ineffective on the Outcome of a

Merger? ...........................................................................687

1. Building Blocks: Bailey v. Vanscot Concrete Co. .....687

2. The Modern Texas View: TXO Production Co. v.

M.D. Mark, Inc...........................................................688

3. The Reach of the Term ―Merger‖: The Effect of

McAleer ......................................................................691

4. Expanding the Reach of the Modern View: The

Allen Holding .............................................................692

5. Drawing Conclusions from the TXO Line..................694

B. PPG Industries, Inc. and Its Lineage: When and Why

Courts Outside of Texas Interpret Mergers To Violate

Anti-Transfer and Anti-Assignment Provisions ...............695

1. The Foundation: PPG Industries, Inc. v. Guardian

Industries Corp. .........................................................695

2. Careful Drafting: The Salgo Court‘s Business

Experience Analysis...................................................696

3. An Intermediate View: Determining Star Cellular‘s

Effect on the Scope of TXO .......................................699

*

B.A., Pennsylvania State University, 2006; candidate, J.D., Baylor Law School, 2009.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

684 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

4. Different Interpretations of the Same Statute: The

Cincom Court‘s Analysis of the Ohio Merger

Statutes .......................................................................701

5. Why the Disparity: Reaching Conclusions on the

PPG Line ...................................................................702

III. STATE MERGER STATUTE SURVEY: TRACKING THE ABILITY

OF THE SURVIVING ENTITY TO EXERCISE CONTRACT

RIGHTS OBTAINED VIA MERGER ............................................703

A. State Statutes Which Resemble the Model Business

Corporation Act’s “Vesting” Language .........................704

B. State Statutes Based on the Model Business

Corporation Act Which Add Specific Statutory

Language Regarding Transfer and Assignment ..............707

C. State Statutes Which Do Not Mention “Vesting” ............709

D. State Statutes Which Provide Specific Boundaries

Concerning Contractual Language .................................711

E. What Are the Implications from the Different

Language? .......................................................................712

IV. OUTWITTING THE TEXAS MERGER STATUTES: IF A MERGER

DOES NOT EFFECT A ―TRANSFER‖ UNDER TEXAS LAW,

DOES IT EFFECT A ―TRANSFER‖ UNDER THE UNIFORM

FRAUDULENT TRANSFER ACT? ...............................................713

V. PUTTING TOGETHER THE PIECES: THE POSSIBILITY THAT A

TEXAS COURT COULD INTERPRET A MERGER TO EFFECT A

TRANSFER OR ASSIGNMENT ....................................................716

VI. CONCLUSION .............................................................................718

I. INTRODUCTION

A basic presumption of contract law is that rights under agreements are

assignable unless the agreement itself, a statute, or public policy provides

otherwise.

1

This presumption ensures that each party to the contract gets

precisely what they bargained for.

2

Additionally, the free transferability of

1

3 E. ALLAN FARNSWORTH, FARNSWORTH ON CONTRACTS §§ 11.2, 11.4 (2d ed. 1998);

U.C.C. § 2-210(2) (2008); 3 RESTATEMENT (SECOND) OF CONTRACTS § 317(2) (1981).

2

See Tenneco Inc. v. Enter. Prods. Co., 925 S.W.2d 640, 646 (Tex. 1996).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 685

contract rights encourages parties to enter into business transactions

because the parties are assured that all the rights, remedies, and benefits

incidental to the property being acquired will transfer with the property.

3

Under this presumption, when multiple business entities are merged, the

rights, powers, interests, and properties continue their existence, ultimately

to be exercised by the surviving entity.

4

Without this presumption, it would

not be efficient to merge business entities due to the additional legal costs

and efforts required to ensure proper transfer and assignment of such rights,

powers, and interests involved. When one or more parties choose to limit

the ability of the other parties to assign and transfer rights, it is commonly

accomplished through the inclusion of anti-assignment and anti-transfer

provisions.

5

Thus, while the presumption of free-assignability creates a

basis for mergers, the efficient merger only arises when the contracting

parties embody this presumption through express contractual language

describing the effect of a merger on pre-existing anti-assignment and anti-

transfer clauses. By addressing pre-existing contractual language, the

merging entities ensure that rights, powers, interests, and properties shift

between the entities as intended in the agreement of merger.

Unfortunately, not every contract addresses the ability to assign and

transfer certain rights. When a contract fails to address transfers or

assignments and a later merger causes argument over the ability to assign or

transfer, the state merger statute governing the transaction is used to fill in

the gaps.

6

Thus, while companies generally merge with the expectation that

the company resulting from the merger will have complete freedom to

exercise the rights and powers of both the acquiring company and the

acquired company, historically, the extent of such exercise depended upon

the intention of the legislature as manifested in the statute governing the

matter.

7

Absent any agreement to the contrary, the consolidated company

3

Hinton Prod. Co. v. Arcadia Exploration & Prod. Co., 261 S.W.3d 865, 871 (Tex. App.—

Dallas 2008, no pet.).

4

See Novartis Seeds, Inc. v. Monsanto Co., 190 F.3d 868, 872 (8th Cir. 1999).

5

Note, Effect of Corporate Reorganization on Nonassignable Contracts, 74 HARV. L. REV.

393, 394–95 (1960).

6

Sears, Roebuck & Co. v. AIG Annuity Ins. Co., 270 S.W.3d 632, 634 (Tex. App.—Dallas

2008, pet. filed).

7

See Barreiro v. Bank of Italy Nat‘l Trust & Sav. Ass‘n, 13 P.2d 1017, 1023 (Cal. App.

1932), aff’d on reh’g, 14 P.2d 786 (Cal. App. 1932) (In re Barreiro‘s Estate); Pa. Utils. Co. v.

Pub. Serv. Comm‘n, 69 Pa. Super. 612, 1918 WL 2303, at *2 (Super. Ct. 1917); Yazoo & M. V.

R. Co. v. Sunflower County, 87 So. 417, 418 (Miss. 1921).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

686 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

can only have the rights and powers that the statute expressly or impliedly

confers upon it.

8

Implicit in this statement is the general presumption that

two parties bargaining at arm‘s-length can always agree to contract around

the language of the applicable merger statutes and nullify their effect. The

basis for this Comment arises from situations where the contract

ambiguously addresses the issues of assignability and transferability of

contract rights.

The leading case addressing this issue in Texas is TXO Production Co.

v. M.D. Mark, Inc., which held that a merger does not constitute a transfer

or assignment in the state of Texas.

9

TXO involved the merger of a

subsidiary (TXO Prod. Co.) into its parent (Marathon) and left a lingering

issue of whether a Texas court would come to a different conclusion based

on similar facts if the merger involved unrelated entities.

10

The Texas

Business Corporation Act and the Texas Business Organizations Code both

answer this issue, at least in cases where the Texas merger statutes are

relied upon in the resolution of the case.

11

While discussed at length in

Section II of this Comment, it is important to introduce TXO here because

the issues arising under the facts of TXO are the same issues sought to be

resolved in this Comment. Additionally, it is one of the few Texas cases

addressing these issues and provides persuasive precedent that Texas

practitioners may use in addressing this matter with their clients.

This Comment seeks to illustrate two distinct lines of cases arising from

fact patterns similar to TXO. The main issue in this Comment is when and

why certain anti-transfer and anti-assignment clauses have greater effects

on mergers than others, and when those effects result from court

interpretation of a contract versus application of state statutory language.

Part II addresses this issue by looking at several lines of cases that provide

reasoning and conclusions similar to either TXO Production Co. v. M.D.

Mark, Inc., or PPG Industries, Inc. v. Guardian Industries Corp.

12

While

the methodology appears to be unique to this Comment, for purposes of

simplicity and organization, the cases discussed are referred to as following

8

In re Barreiro’s Estate, 13 P.2d at 1023.

9

999 S.W.2d 137, 143 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 1999, pet. denied).

10

Id. at 141.

11

See Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06, § A(2) (Vernon Supp. 2008); Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code

Ann. § 10.008(a)(2) (Vernon 2007).

12

TXO Prod. Co., 999 S.W.2d at 143; PPG Indus., Inc. v. Guardian Indus. Corp., 597 F.2d

1090 (6th Cir. 1979).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 687

the TXO or PPG lines. Part III includes analysis of merger statutes from

across the county and illustrates multiple situations where the effect of a

merger on a contract of a merging party is interpreted using state merger

statutes. Part IV addresses the potential complications that the Uniform

Fraudulent Transfer Act may have upon the meaning of ―transfer‖ as it

pertains to the effect of a merger in Texas. Part V explores the rigidity of

the Texas view regarding the effect of a merger on anti-assignment and

anti-transfer language. Finally, Part VI reaches a conclusion from the case

law, statutes and commentaries consulted in writing this Comment.

In Texas, the main issue is well-settled by statute.

13

At least in

situations where the Texas merger statutes are used to fill in gaps and

ambiguities with respect to the effect of a merger on assignment and

transfer of rights, Texas courts are likely to follow TXO and hold that a

merger is not a transfer or assignment.

14

However, a situation could arise

where implications of public policy and the potential outcome of following

the TXO holding may cause a court to be reluctant to follow TXO. In

Texas, as well as other states, there appears to be room for this situation to

arise when the issue is transferability of rights under limited liability

company and partnership agreements.

II. TWO DISTINCT INTERPERTATIONS: DECIPHERING THE TXO AND

PPG LINES OF CASES

A. The TXO Line: Why Have Texas Courts Historically Interpreted

Anti-Assignment and Anti-Transfer Provisions As Being

Ineffective on the Outcome of a Merger?

1. Building Blocks: Bailey v. Vanscot Concrete Co.

In Texas, traditionally, state courts having the opportunity to determine

the effect of a merger on anti-assignment and anti-transfer language allow

the acquiring or surviving company to operate under the contract with the

full rights, privileges, powers, and interests which both companies enjoyed

prior to the business transaction that brought the companies together.

In Bailey v. Vanscot Concrete Co., Vanscot Concrete Company and

Hoveringham USA, Inc. were merged into Cen-Tex Ready-Mix Concrete

13

Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06, § A(2); Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code Ann. § 10.008(a)(2).

14

TXO Prod. Co., 999 S.W.2d at 142–43.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

688 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

Company, and later changed its name to Tarmac Texas, Inc.

15

Three

months after the articles of merger were filed, Bailey was allegedly injured

by contaminated concrete delivered by a truck with the inscription

―Express/Pennington‖ on the side.

16

After determining that Vanscot was

the owner of the company, Bailey filed suit against Vanscot Concrete

Company.

17

Vanscot asserted a defect of parties and denied under oath that

it was a corporation.

18

The Texas Supreme Court stated that ―Vanscot had no actual or legal

existence at the time of Bailey‘s accident.‖

19

The court, in addressing the

party designations argument, ultimately held: ―In a merger, the privileges,

rights, and duties of the corporation are transferred to the surviving

corporation and are there continued and preserved.‖

20

Thus, the court

recognized the basic concept that, in Texas, the surviving corporation

succeeds to all the rights, powers, and privileges of all corporations

involved in the merger.

21

More importantly, the court characterized the

effect of the merger as being a ―transfer‖ of rights, powers, and privileges.

22

While the Texas Supreme Court‘s use of the term ―transfer‖ cannot amount

to anything more than dicta in a holding resolving party designations,

whether or not the court purposely selected the term ―transfer‖ can only be

determined if and when the issue is ever before the Texas Supreme Court.

2. The Modern Texas View: TXO Production Co. v. M.D. Mark,

Inc.

TXO is quintessential to any discussion on the effect of Texas merger

statutes on the interpretation of anti-assignment and anti-transfer

15

894 S.W.2d 757, 758 (Tex. 1995).

16

Id.

17

Id.

18

Id. During trial, Bailey was granted leave to file a trial amendment to make the defendants

―Vanscot Concrete Company d/b/a/ Express/Pennington Concrete Company.‖ In response to the

amendment, Vanscot moved for a directed verdict at the conclusion of Bailey‘s case on the

grounds that Vanscot had ceased to exist upon the merger with Hoveringham USA, Inc. and thus,

Bailey had sued the wrong party. The trial court held for Bailey and the court of appeals reversed.

19

Id. at 759.

20

Id. (citing Vulcan Materials Co. v. United States, 446 F.2d 690, 694 (5th Cir. 1971)).

21

Id.

22

Id.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 689

provisions.

23

Few Texas courts have had the chance to interpret the effect

of a merger on anti-assignment or anti-transfer provisions, thus, the current

state of the law in Texas is reflected by TXO. Furthermore, because the

Texas Supreme Court denied review, and the opportunity to create binding

precedence for this issue, TXO remains the most widely used precedent on

this issue.

24

In TXO Production Co. v. M.D. Mark, Inc., the 14th District Court of

Appeals in Houston determined whether the merger of Marathon and TXO

constituted a transfer of data in violation of the anti-transfer and other non-

disclosure provisions of the contract originally entered into by TXO and

PGI.

25

TXO Production Co. (―TXO‖) was an oil and gas exploration

company and a wholly-owned subsidiary of Marathon Oil Co.

(―Marathon‖).

26

PGI, a geophysical consulting firm, and TXO entered into

a series of contracts from 1979 to 1989 allowing TXO to use certain data

from seismic surveys conducted by PGI.

27

Each contract contained the

following provision: ―[The data] shall not be sold, traded, disposed of, or

otherwise made available to third parties.‖

28

Following the series of

contracts, Marathon and TXO merged, and TXO informed PGI that the data

would be automatically transferred to Marathon pursuant to the applicable

merger statutes.

29

M.D. Mark, Inc., the assignee of PGI, eventually brought

suit against TXO.

30

The trial court held that the merger was a transfer of the seismic data

and constituted a breach of the parties‘ agreements and TXO appealed.

31

The court of appeals first analyzed PPG Industries, Inc v. Guardian

Industries Corp.

32

and Nicolas M. Salgo Associates v. Continental Illinois

Properties

33

before distinguishing the reasoning and outcome of both

because the corporations in PPG and Salgo merged into unrelated entities,

23

TXO Prod. Co. v. M.D. Mark, Inc., 999 S.W.2d 137 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.]

1999, pet. denied).

24

Id.

25

Id. at 143.

26

Id. at 138.

27

Id.

28

Id.

29

Id.

30

Id.

31

Id.

32

597 F.2d 1090 (6th Cir. 1979).

33

532 F. Supp. 279 (D.D.C. 1981).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

690 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

and TXO involved the merger of a subsidiary and a parent.

34

Next, the TXO

court provided analysis of Article 5.06 of the Texas Business Corporation

Act, which states that the rights, title, and interest in property of the

merging corporations vest in the surviving corporation upon merger without

further act or deed and without any transfer having occurred.

35

Based on

the language of the statute and the legislative history pertaining to Article

5.06, the TXO court concluded:

Under the merger statutes

36

it is clear that all of TXO‘s

interests vested in Marathon immediately upon the merger.

Further, under these provisions there is no transfer of the

rights of the merging corporation; rather, the rights vest

automatically and without further action . . . . [W]e will not

imply a violation of the non-disclosure agreement in light

of the parties‘ failure to address this situation.

37

While TXO holds that mergers do not trigger anti-assignment or anti-

transfer language in contracts based on Texas law, the court‘s holding was

narrow enough that variations could occur in the future. First, the court

noted, ―The parties could have easily specified that the non-disclosure

provision was implicated by a statutory merger, but they chose not to do

so.‖

38

Recognizing that, in situations where the parties want to include

effective anti-transfer or anti-assignment provisions, carefully drafted

provisions dictating when and how the clauses are enforceable will allow

the parties to circumvent the holding of TXO. Second, the court specifically

distinguished the PPG and Salgo courts because the corporations in those

cases merged into unrelated entities.

39

Thus, an argument based on PPG,

and against TXO, could be made when a corporation in a lawsuit merges

into an unrelated entity. Furthermore, in a situation causing a similar

outcome to the Salgo case, the equity of a holding which forces a

partnership to accept a partner it does not want may cause a Texas court to

34

TXO Prod. Co., 999 S.W.2d at 141 (―We disagree with the reasoning and outcome of PPG

and Salgo. . . . [T]hose cases are distinguishable because there, the corporations merged into

unrelated entities.‖).

35

Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06, § A(2) (Vernon Supp. 2008).

36

DEL. CODE ANN., tit. 8 § 259 (2001); OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 1701.82(A)(3) (LexisNexis

2008); Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06, § A(2).

37

TXO Prod. Co., 999 S.W.2d at 142–43.

38

Id. at 143.

39

Id. at 141.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 691

feel reluctant in applying TXO due to express language regarding

admittance as a partner under Texas law.

40

For further discussion on the

intended result under Texas law, see Section IIIB and the discussion on the

official comments to Article 5.06 of the Texas Business Corporation Act.

41

3. The Reach of the Term ―Merger‖: The Effect of McAleer

In McAleer v. Eastman Kodak Co., the Amarillo Court of Appeals

determined whether Eastman Kodak Co. (―Kodak‖) had the ability to freely

assign rights received under an easement agreement (the ―agreement‖) with

McAleer to Kodak‘s newly formed corporation—the Eastman Chemical

Company (―Chemical‖)—as part of a stock spin-off.

42

The main issue in

the case was whether the term ―merger‖ as defined in the easement

agreement between McAleer and Eastman Kodak included a ―stock spin-

off‖ or just the traditional merger in which two entities become one.

43

McAleer is important to the resolution of the issues in this Comment

because it recognizes the effect that efficient drafting can have on the

resolution of a conflict involving an anti-assignment provision.

Kodak and McAleer entered into an easement to provide Kodak the

ability to build and operate a pipeline across certain real property owned by

McAleer.

44

The agreement stated that permission to enter the property,

―may not be assigned or conveyed,‖ but also stated that if Kodak merged or

consolidated with another corporation or was otherwise acquired, ―the

resulting or succeeding corporation shall succeed to this permit and shall be

personally liable.‖

45

The conflict arose when Kodak formed Chemical and

allowed Chemical to succeed to the interests that Kodak owned under the

easement.

46

Because Chemical was formed through a stock spin-off,

McAleer argued that the transaction was an unwarranted assignment

because use of the term ―merger‖ was not intended to mean anything other

40

Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code Ann. § 152.201 (Vernon 2007) (―A person may become a partner

only with the consent of all partners.‖).

41

See infra Part III.B.

42

No. 07-02-0015-CV, 2002 WL 31686682, at *4 (Tex. App.—Amarillo Dec. 2, 2002, no

pet.) (not designated for publication).

43

Id.

44

Id. at *1.

45

Id.

46

Id.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

692 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

than, ―the combination of two entities into one.‖

47

The court, however,

determined ―the definition of merger should be a broad one and [because

the law does not favor forfeitures] that a merger should not violate a non-

assignability clause.‖

48

The court held that ―the only reasonable

construction‖ of the contract was finding the stock spin-off did not violate

the anti-assignment provision.

49

McAleer provides further emphasis on the rule that a Texas court will

only construe a contract to end in forfeiture if there is no other reasonable

interpretation of the contract.

50

When drafting anti-assignment and anti-

transfer provisions, the Texas practitioner must understand that Texas

courts are not willing to enforce anti-assignment and anti-transfer language

when there is a reasonable interpretation of the contractual language that

results in a holding similar to TXO. Thus, when drafting the definition

sections of an agreement involving anti-assignment or anti-transfer

provisions, the Texas practitioner must use tedious foresight to include all

possible explanations of the term ―merger‖ that may be able to trigger the

enforcement of such a provision. The McAleer court implies that had the

parties wanted stock spin-offs to trigger anti-assignment and anti-transfer

provisions, the parties to the contract simply needed to expressly state, ―a

merger will not include a stock spin-off.‖

51

McAleer, like TXO, recognizes

that when a court is not forced to use Texas statutory language to fill in the

gaps or resolve an ambiguity within a contract or agreement, the contracting

parties have the ability to choose the effect a merger will have upon any

assignments or transfers of rights and privileges contracted for under the

agreement.

4. Expanding the Reach of the Modern View: The Allen Holding

Recently, in Allen v. United of Omaha Life Insurance Co., the Fort

Worth Court of Appeals determined the effect of a merger on the

47

Id. at *4.

48

Id.

49

Id. at *5.

50

Id. at *4; see TSB Exco, Inc. v. E.N. Smith, III Energy Corp., 818 S.W.2d 417, 422 (Tex.

App.—Texarkana 1991, no writ); Cambridge Oil Co. v. Huggins, 765 S.W.2d 540, 543 (Tex.

App.—Corpus Christi 1989, writ denied).

51

See McAleer, 2002 WL 31686682, at *4.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 693

beneficiary designation of a ―key-man‖ life insurance policy.

52

While there

was no anti-assignment or anti-transfer clause at issue in this case, Allen

provides insight into one Texas court‘s interpretation of the effect of a

merger on the transfer of a life insurance contract from the non-surviving

entity to the surviving entity. Allen is important to the Texas practitioner

because in some instances, life insurance contracts may be overlooked

when expressly drafting the effect of a merger on specifically defined

rights, privileges, and properties. The McAleer decision should also be

considered when looking at Allen, as McAleer made clear that careful

drafting and meticulous focus on the scope of the term ―merger‖ in a

contract or other agreement can have a tremendous impact on the efficiency

of a merger.

53

Fred Allen was the CEO of CreditWatch Services, L.P. and the

president of CreditWatch Services, L.P.‘s general partner, Stoneleigh

Financial L.L.C.

54

CreditWatch Services, L.P. purchased a ―key man‖ life

insurance policy on Fred‘s life in the amount of $1 million.

55

Fred signed

the application in both his individual and official capacities and designated

CreditWatch Services, L.P. as the policy‘s sole beneficiary.

56

One year

later, CreditWatch Services, L.P. merged with CreditWatch Services, Ltd.,

an Ohio limited liability company and changed its name to CreditWatch

Services LLC, but the insurance policy‘s beneficiary designation was never

changed from CreditWatch Services, L.P.

57

Following Fred‘s death, United

of Omaha Life Insurance Company, one of the named defendants in the

case, issued a check payable to ―CreditWatch Services‖ and CreditWatch

Services LLC deposited the check into one of its accounts.

58

Judy Allen,

the decedent‘s wife, brought suit for tortious interference with an

inheritance and conspiracy to commit fraud, and argued that because the

policy‘s designated beneficiary did not exist when Fred died, United should

52

236 S.W.3d 315, 319 (Tex. App.—Fort Worth 2007, pet. denied); 34A AM. JUR 2D Fed.

Taxation ¶ 143,770 (2009) (―Many corporations and partnerships carry key-man life insurance

policies on top executives and officers-stockholders. The key man usually takes out the policy,

and then assigns it to the corporation. The policy proceeds are typically excluded from the key

man‘s estate [at death, with some exceptions]‖).

53

See McAleer, 2002 WL 31686682, at *1, *4.

54

Allen, 236 S.W.3d at 319.

55

Id.

56

Id.

57

Id.

58

Id.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

694 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

have paid the policy proceeds to Fred‘s estate.

59

The court held that,

―CreditWatch Services, L.P.‘s rights as the life insurance policy‘s

beneficiary vested in CreditWatch Services, Ltd. when the two entities

merged.‖

60

The court specifically reiterated and made reference to the basic

Texas merger rule from the holding in Bailey v. Vanscot Concrete, stating

that the surviving entity succeeds to all privileges, powers, rights, and

duties originally held by all parties to the merger.

61

5. Drawing Conclusions from the TXO Line

What does the practitioner gain from the TXO line of cases? One gains

the understanding that in Texas state courts, the language of the contract

will most often be interpreted to reach a conclusion that reflects the basic

rule—that a merger does not trigger an anti-assignment or anti-transfer

clause—but also avoids forfeiture, even if such avoidance requires the court

to stretch for reasoning. Whether that means the court has to expand the

interpretation of the term ―merger‖ or ―consolidation,‖ shift blame to the

failure of the contracting parties to foresee possible business transactions

and changes in control, or extend the beneficiary designations in a life

insurance policy, the court will take every opportunity to circumvent

provisions that trigger ―anti‖ provisions and preclude the surviving entity

from realizing the benefits of the contract(s) at issue. The TXO line of cases

presents only one side of the conflict over this issue across the United

States. The other side of the conflict is built on a foundation established in

PPG Industries Inc., v. Guardian Industries Corp. exactly twenty years

prior to the decision in TXO.

62

Analysis of the PPG line of cases provides

the practitioner with knowledge of the jurisdictions and factual

circumstances that lead some courts to reach holdings entirely antithetical to

TXO.

59

Id. at 319–20.

60

Id. at 322.

61

Id.

62

597 F.2d 1090 (6th Cir. 1979).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 695

B. PPG Industries, Inc. and Its Lineage: When and Why Courts

Outside of Texas Interpret Mergers To Violate Anti-Transfer and

Anti-Assignment Provisions

Outside of Texas, state and federal courts have aligned themselves with

both sides of the controversy. However, in jurisdictions that conclude a

merger does constitute a transfer or assignment, the reasoning has often

mirrored the Texas courts‘ yet resulted in antithetical conclusions. While

the courts composing the PPG line seem to take a hard line approach, the

courts cannot seem to resist providing more justification as to why.

Whether its strict adherence to the basic tenets of intellectual property

rights, an inequitable outcome for a partnership, or an uneasy feeling about

causing unwarranted risk, the PPG line provides numerous holdings that

may be used to cause reluctance towards TXO in Texas.

1. The Foundation: PPG Industries, Inc. v. Guardian Industries

Corp.

PPG Industries, Inc. v. Guardian Industries Corp. is the cornerstone

case holding that a merger is an assignment and transfer and violates anti-

assignment and anti-transfer language in a contract.

63

The PPG court

decided the issue of whether the surviving or resultant corporation in a

statutory merger acquires patent license rights of the constituent

corporations when the patent license has specific anti-assignment

language.

64

In 1964, PPG Industries, Inc. (―PPG‖) entered into a patent license

agreement with Permaglass, Inc. (―Permaglass‖), which allowed

Permaglass to make use of PPG‘s ―Gas Hearth Systems.‖

65

The licensing

agreement contained the following anti-assignment provision, ―9.2 This

Agreement and the license granted by PPG to PERMAGLASS hereunder

shall be personal to PERMAGLASS and non-assignable except with the

consent of PPG first obtained in writing.‖

66

In 1969, Permaglass and

Guardian Industries, Corp. (―Guardian‖) merged pursuant to Ohio and

Delaware laws.

67

In the merger agreement, Permaglass represented that,

63

Id. at 1096.

64

Id. at 1091.

65

Id. at 1091–92.

66

Id. at 1092.

67

Id.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

696 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

―Permaglass is the owner, assignee or licensee of such patents, . . . [A]nd

Permaglass has not received any notice of conflict with the asserted rights

of third parties relative to the use thereof.‖

68

Following the merger, PPG

filed suit for patent infringement against Guardian.

69

Guardian asserted that

it had succeeded to all the rights, powers, and ownerships of Permaglass,

and as Permaglass‘ successor was legally entitled to operate under the

licensing agreement.

70

The district court determined that no transfer or

assignment had occurred, but rather that ―Guardian acquired these rights by

operation of law under the merger statutes of Ohio and Delaware,‖ and PPG

appealed.

71

The PPG court, like the TXO court, interpreted Ohio and Delaware

merger statutes to bring resolution to the issue of the effect of a merger on

assignments and transfers. However, unlike the TXO court, the PPG court

found the ―shall be vested‖ language in the Delaware statute to mean, ―the

underlying property of the constituent corporations is transferred to the

resultant corporation upon the carrying out of the consolidation or

merger . . . ,‖ ultimately finding that the merger was effected by the parties

and the transfer was a result of their act of merging.

72

The PPG court also

noted whether or not the merger takes place by operation of law or

otherwise, it still effects a transfer in violation of anti-assignment and anti-

transfer language.

73

Notably, in PPG, the 6th Circuit interpreted merger

statutes from two of the same states as the TXO court did, but came to an

entirely different interpretation. PPG dictates that different courts of

appeals throughout the country, and perhaps even in Texas, could come to

different conclusion about the effect of merger statutes on anti-assignment

and anti-transfer provisions post-merger.

2. Careful Drafting: The Salgo Court‘s Business Experience

Analysis

Nicolas M. Salgo Associates v. Continental Illinois Properties, is

another of the oft-cited cases holding a merger does constitute a transfer and

68

Id. at 1093.

69

Id.

70

Id.

71

Id.

72

Id. at 1096 (quoting Koppers Coal & Transp. Co. v. United States, 107 F.2d 706, 708 (3d

Cir. 1939)) (emphasis added by PPG court).

73

Id.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 697

assignment in violation of anti-assignment and anti-transfer provisions.

74

Salgo expands upon the holding from PPG by introducing the factors of

business experience and drafting abilities of the parties to the merger.

Salgo appears to be unique in making use of such factors in reaching a

conclusion, but also serves to reiterate the proposition that practitioners

must be extremely careful when drafting contracts as their effect on future

business transactions is often vital.

Nicolas M. Salgo Associates (―NMSA‖) and Continental Illinois

Properties (―CIP‖) were the general partners in Watergate Improvement

Associates (―WIA‖).

75

Section 21.0 of the limited partnership agreement of

WIA stated, ―[N]o Partner shall sell, assign, pledge, hypothecate or

otherwise encumber or dispose of all or any part of its interest in this

Partnership (including any beneficial interest therein), except by will or by

operation of law on death, without prior written consent of both General

Partners . . . .‖

76

In 1979, Bouverie Properties, Inc. (―BPI‖) acquired all the

outstanding common stock of CIP and gained effective control of CIP.

77

Two years later, CIP merged into BPI and became Pan American

Properties, Inc. (―PAP‖).

78

At no time prior to execution did CIP seek

NMSA‘s consent to the stock sale or the merger, and this resulted in NMSA

filing suit against CIP and PAP.

79

The defendants, CIP and PAP, argued that, even though the term

―transfer‖ was used in the heading of Section 21.0, the parties‘ (NMSA and

CIP) failure to include the actual term ―transfer‖ in the body of the Section

indicated that 21.0 was not meant to apply to a ―transfer‖ of interest, but

only an ―assignment‖ or ―disposition‖ of interest.

80

The court determined

that the scope of Section 21.0, when taking the entire contract into

consideration, did include transfers of interest.

81

Having determined that a

transfer of interest took place, the court raised another important issue,

74

532 F. Supp. 279, 282–83 (D.D.C. 1981).

75

Id. at 280.

76

Id.

77

Id.

78

Id. at 280–81.

79

Id.

80

Id.

81

Id. at 282.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

698 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

whether a merger by operation of law constitutes a transfer of interest for

purposes of Section 21.0.

82

The Salgo court declared the 6th Circuit‘s approach in PPG to be most

rational way to find a resolution to this issue. Following the PPG court‘s

analysis, the Salgo court interpreted the District of Colombia statute

governing the partnership agreement between NMSA and CIP.

83

In

analyzing the statute, the court concluded that the lack of consent prior to

the merger effectively forced NMSA to accept a new partner without its

consent, which ran counter to the language of the statute.

84

The Salgo

opinion is one of the few to analyze the experience and capacity of the

contracting parties, which noted that ―. . . both parties involved . . . are

extremely experienced business entities and should be savvy to the

importance of accurately drafting contracts.‖

85

Taking the business savvy

of the contracting parties into consideration, the Salgo court concluded that

the parties could have provided for certain exceptions to the language of

Section 21.0 if they had intended to protect against certain types of business

transactions. Thus, the court concluded that the merger constituted a

prohibited transfer in violation of the contract.

86

Salgo, much like PPG,

continues to enforce the fact that different courts are likely to establish

different interpretations of linguistically similar contracts.

82

Id.

83

Id. at 283 (referring to D.C. CODE § 41-317(g): ―No person can become a member of the

partnership without the consent of all the partners.‖).

84

Id. While outside the scope of this Comment, I find it incredibly interesting that none of the

cases dealing with this issue which involve partnerships include any discussion on the distinction

between transfer of a partnership interest (i.e. the economic interest) and the effect on the

individual‘s status as partner. Although a merger may transfer an economic interest to a partner

whom the current partners did not wish to accept as their partner (this was one of the reasons that

the Salgo court concluded the way it did), the economic interest is separate and distinct from the

individual‘s actual status as a partner in the partnership. While a merger can circumvent certain

rules, a merger cannot change a person‘s status from ―individual‖ to ―partner‖ absent a unanimous

vote from the existing partners. See Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code Ann § 152.201 (Vernon 2007); UNIF.

FRAUDULENT TRANSFER ACT § 401(a)(2)(i) (1997).

85

Id.

86

Id.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 699

3. An Intermediate View: Determining Star Cellular‘s Effect on

the Scope of TXO

In 1993, the Delaware Chancery Court decided Star Cellular Telephone

Co. v. Baton Rouge CGSA, Inc.,

87

and while the opinion was not reported,

the reasoning of the court lays the groundwork for the possibility that other

Texas courts may interpret the Texas merger statute differently than the

TXO and Allen courts have.

Star Cellular Telephone Company, Inc.

(―Star‖) and Capitol Cellular, Inc. (―Capitol‖; collectively the ―Plaintiffs‖)

were limited partners in Baton Rouge MSA Limited Partnership, a

Delaware limited partnership (the ―Partnership‖). Baton Rouge CGSA, Inc.

(―Baton Rouge Inc.‖) was the original general partner (and a limited

partner) and was a wholly-owned subsidiary of BellSouth Mobility Inc.

(―BellSouth‖).

88

The partnership agreement contained anti-transfer

language which stated that a general partner could only ―transfer‖ its

interest as a general partner upon written notice to all the other Partners and

a unanimous affirmative vote.

89

In 1991, seven years after the original partnership agreement was

signed, Baton Rouge Inc. was merged into Louisiana CGSA Inc.

(―Louisiana Inc.‖), another wholly owned subsidiary of BellSouth.

90

One

year later, the Plaintiffs brought suit against Baton Rouge Inc. and

Louisiana Inc. alleging the merger effected a prohibited transfer of Baton

Rouge Inc.‘s general partnership interest under the Partnership agreement

and thus, Capitol was the rightfully elected general partner.

91

The

defendants asserted that under Georgia law (which governed the merger)

the merger did not constitute a ―transfer‖ under the agreement because the

term ―merger‖ was never referenced in the agreement, that even if it was a

―transfer‖ it was authorized under the agreement, and finally that anti-

transfer provisions cannot be enforced against a transfer that ―has no

adverse effect on the other contracting party.‖

92

The Star Cellular court

concluded that the merger was not a ―transfer‖ for purposes of the anti-

transfer provision because ―where an anti-transfer clause . . . does not

explicitly prohibit a transfer of property rights to a new entity by a

87

Civ. A. No. 12507, 1993 WL 294847 (Del. Ch. Aug. 2, 1993) (unpublished op.).

88

Id. at *1.

89

Id. at *5.

90

Id. at *1.

91

Id.

92

Id. at *3.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

700 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

merger . . . and the transfer itself creates no unreasonable risks for the other

contracting parties, the court should not presume that the parties intended to

prohibit the merger.‖

93

While the Star Cellular case seems antithetical to the PPG and Salgo

opinions, it provides an important conclusion stating if the parties had

elected to include ―merger‖ in the anti-transfer clause, a merger would have

triggered the clause. The court indicated that some mergers could be

transfers when such a transfer resulted in a material increase of risk or

harm.

94

Additionally, the Georgia statute in use at the time of the merger

had language similar to the current merger language in the Texas Business

Organizations Code and the unofficial comment to the section mirrored the

language expressed in the official comments to the Texas Business

Corporation Act as detailed in Section IIIB of this Comment.

95

The

Georgia merger statute stated that the property of the disappearing

corporation ―is vested in the surviving corporation‖ and the unofficial

comment to Section 14-2-1106(a)(2) [the effect of merger section] stated

that ―[a] merger is not a conveyance or transfer.‖

96

The TXO court

interpreted similar language in coming to the conclusion in TXO, which

leaves open the possibility that a court interpreting ―transfer‖ in a case

where the merger presented unreasonable risk, could decide to extend the

definition of the term ―transfer‖ to permit anti-transfer provisions to take

effect. Thus, while Star Cellular follows the reasoning in TXO, it is an

intermediate view because the court expressly details that other conclusions

are possible outside of holding that a merger does not constitute a transfer

or assignment.

93

Id. at *8.

94

Id. at *11 (―In these circumstances, the Court will not attribute to the contracting parties an

intent to prohibit the Merger where the transaction did not materially increase the risks to or

otherwise harm the limited partners.‖).

95

Id. at *6 (The unofficial comment to the section states that ―[a] merger is not a conveyance

or transfer[.]‖); see also Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06 (Vernon 2003) (The official comment

to Article 5.06 of the Texas Business Corporations Act, in use during the court‘s analysis in TXO

Prod. Co. v. M.D. Mark, Inc., stated ―Article 5.06 was amended to make clear that while a merger

vests the rights [and] privileges . . . this is accomplished without a transfer or assignment having

occurred.‖).

96

GA. CODE ANN. § 14-2-1106(a)(2) cmt. (West 2003 & Supp. 2008).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 701

4. Different Interpretations of the Same Statute: The Cincom

Court‘s Analysis of the Ohio Merger Statutes

In January 2007, the United States District Court for the Southern

District of Ohio decided Cincom Systems, Inc. v. Novelis Corp.

97

The issue

in this case was whether the direct merger of Alcan Aluminum Corporation

(―Alcan Ohio‖) into Alcan Corporation, which then merged into its

subsidiaries, resulted in an impermissible transfer of a non-transferable

computer software license agreement (the ―agreement‖) originally

contracted for between Alcan Ohio and Cincom Systems (―Cincom‖).

98

In

1989, Alcan Ohio entered into a software license agreement with Cincom,

which prohibited the transfer of rights under the agreement without

Cincom‘s prior written consent.

99

In 2003, Alcan Ohio merged into its

corporate affiliate, Alcan Corporation, who subsequently merged into its

three Texas subsidiaries: Alcan Products Corp., Alcan Primary Products

Corp., and Alcan Fabrication Corp.

100

The business of Alcan Ohio was

predominantly assumed by the Alcan Fabrication Corp. subsidiary (in 2005,

Alcan Fabrication Corp. changed its name to Novelis Corporation

(―Novelis‖)).

101

At no time during any of the aforementioned business transactions did

Alcan Ohio, Alcan Corporation, or Novelis make any attempt to obtain

Cincom‘s consent to transfer the agreement, and Cincom sued all three for

infringement.

102

The defendants argued that under Ohio‘s merger statute,

the events leading to the creation of Novelis did not result in a transfer of

the agreement from Alcan Ohio to Novelis.

103

Ohio‘s merger statute,

modeled after the Model Business Corporation Act §11.07, states: ―[t]he

surviving or new entity possesses all assets and property . . . rights,

privileges, immunities, powers . . . all of which are vested in the surviving

or new entity without further act or deed.‖

104

Persuaded by the PPG court‘s

reasoning, the Cincom court decided that at the point when Alcan Ohio was

97

No. 1:05CV152, 2007 WL 128999, at *1 (S.D. Ohio Jan 12, 2007).

98

Id.

99

Id.

100

Id.

101

Id.

102

Id.

103

Id.

104

Id. at *2–3; OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 1701.82(A)(3) (LexisNexis Supp. 2008) (emphasis

added).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

702 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

merged out of existence, its rights under the agreement were transferred to

Alcan Corporation and under PPG, ―[t]he merger was effected by the

parties and the transfer was a result of their act of merging.‖

105

The Cincom

court, interpreting the same Ohio merger statute as the TXO court,

concluded that the series of events leading to the creation of Novelis

Corporation resulted in ―an impermissible transfer to Novelis of the License

Agreement granted to Alcan Ohio by Cincom.‖

106

Cincom presents a

holding entirely antithetical to that of TXO, even though the circumstances

leading to the lawsuit were substantially similar.

5. Why the Disparity: Reaching Conclusions on the PPG Line

PPG, Salgo, Star Cellular, and Cincom provide a second line of cases in

opposition to the TXO line of cases. The PPG line of cases illustrates that

in certain jurisdictions, courts do not apply common law analyses

preventing forfeiture of contract rights in the merger context when

interpreting the scope of anti-transfer or anti-assignment provisions.

107

Rather, the language of the contract controls the court‘s reasoning to the

extent it can, and where this language falls short, the courts are willing to

interpret the intent of the parties‘ regardless of whether the interpretation

results in anti-assignment and anti-transfer provisions taking effect or not.

It is not unreasonable to hypothesize that aspects of the PPG line could

influence a Texas court to hold that a merger does constitute a transfer or

assignment under similar circumstances as those evident in the PPG line of

cases.

108

However, in order to fully understand the disparities, it is vital to

look at the actual statutory language lending rationality between the

antithetical holdings.

105

Cincom, 2007 WL 128999, at *4 (citing PPG Indus., Inc. v. Guardian Indus. Corp., 597

F.2d 1090, 1093 (6th Cir. 1979)).

106

Id. at *6.

107

Not all improper assignments or transfers which trigger enforcement of anti-assignment or

anti-transfer provisions cause forfeiture of the contract. Depending on the contractual language,

there may be fees, liquidated damages, or other remedies provided for. Thus, in some

circumstances, regardless of the court‘s holding, forfeiture is always avoided.

108

See infra note 143.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 703

III. STATE MERGER STATUTE SURVEY: TRACKING THE ABILITY OF

THE SURVIVING ENTITY TO EXERCISE CONTRACT RIGHTS OBTAINED

VIA MERGER

109

All jurisdictions provide that the existence of all entities party to the

merger agreement, with the exception of the new or surviving entity, cease

to exist upon the effective date of the merger.

110

Additionally, all

jurisdictions dictate that the surviving or new entity obtains all the

privileges, rights, immunities and powers subject to the duties and liabilities

inherent in such privileges, rights, immunities and powers.

111

The

differences among states that created the conflict at issue in this Comment

sometimes arise from the states‘ selection of different language used to

describe and explain the effect of a merger on the ability of the surviving

entity to obtain such rights and privileges when outside agreements state

otherwise.

State merger statutes can be broken down into four categories depending

on the selected language used by the state legislatures. The overwhelming

majority of states model their merger statutes on the Model Business

Corporation Act §11.07. Texas and Georgia are the only two states whose

merger statutes specifically dictate a merger takes effect without any

transfer or assignment having taken place.

112

However, cases explained

above call into question the willingness of some courts to accept this

language as a mandatory bar in all situations. Some courts are willing to

stretch the language of the contract in order to circumvent the statutory

language. Pennsylvania and Puerto Rico completely avoid using ―vesting‖

language at all.

113

Virginia is the only state which expressly dictates that

the statute will not apply when contractual language provides the

anticipated result of the parties to the agreement.

114

109

Included in the survey are the 50 United States as well as the U.S. territories of Puerto

Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands. I felt it unnecessary to use the term ―states and territories‖ each

and every time I made an assertion.

110

MODEL BUS. CORP. ACT ANN. § 11.07 note (2008) (statutory comparison).

111

Id.

112

See GA. CODE ANN. § 14-2-1106(a)(2) (West Supp. 2008); see also Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code

Ann. § 10.008(a)(2) (Vernon 2007).

113

See 7 PA. STAT. ANN. § 1606(c) (West 1995); P.R. LAWS ANN. tit. 26, § 2947(1) (2008).

114

See VA. CODE ANN. § 13.1-721(3) (West 2006).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

704 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

A. State Statutes Which Resemble the Model Business Corporation

Act’s “Vesting” Language

The Model Business Corporation Act (the ―MBCA‖) §11.07(a) states,

―[w]hen a merger becomes effective . . . (3)all property owned by, and

every contract right possessed by, each corporation or eligible entity that

merges into the survivor is vested in the survivor without reversion or

impairment.‖

115

The following statutes include ―is vested‖, ―are vested‖, or

―vested‖ language similarly to the MBCA:

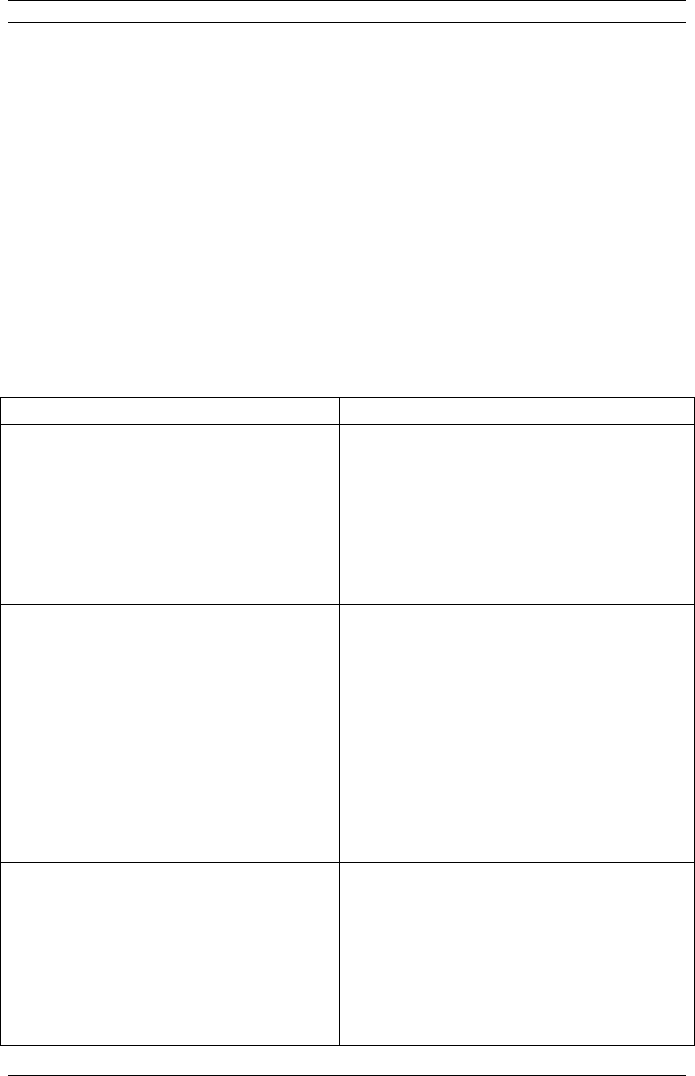

State

Language

Arizona

116

The title to all real estate and other

property owned by each corporation

that is a party to the merger is vested

automatically in the surviving

corporation without reversion or

impairment.

Connecticut

117

All liabilities of each corporation or

other entity that is merged into the

survivor are vested in the survivor.

All property owned by, and every

contract right possessed by, each

corporation or other entity that

merges into the survivor is vested in

the survivor without reversion or

impairment . . . .

Delaware

118

[T]he rights, privileges, powers and

franchises of each of said

corporations, and all property, real,

personal and mixed, and all debts due

to any of said constituent

corporations on whatever account, as

well for stock subscriptions as all

115

MODEL BUS. CORP. ACT § 11.07(a)(3) (2005).

116

ARIZ. REV. STAT. ANN. § 10-1106(A)(2) (2004).

117

CONN. GEN. STAT. ANN. § 33-820(a)(3)–(4) (West 2005).

118

DEL. CODE ANN. tit. 8, § 259(a) (2001).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 705

other things in action or belonging to

each of such corporations, shall be

vested in the corporation surviving or

resulting from such merger or

consolidation . . . .

Florida

119

The title to all real estate and other

property, or any interest therein,

owned by each corporation party to

the merger is vested in the surviving

corporation without reversion or

impairment . . . .

Ohio

120

The surviving or new entity

possesses all assets and property of

every description, and every interest

in the assets and property, wherever

located, and the rights, privileges,

immunities, powers, franchises, and

authority, of a public as well as of a

private nature, of each constituent

entity, and . . . all obligations

belonging to or due to each

constituent entity, all of which are

vested in the surviving or new entity

without further act or deed.

Tennessee

121

All property owned by each

corporation or limited partnership

that is a party to the merger shall be

vested in the surviving corporation or

limited partnership without reversion

or impairment . . .

119

FLA. STAT. ANN. § 607.1106(1)(b) (West 2007).

120

OHIO REV. CODE ANN. § 1701.82(A)(3) (LexisNexis Supp. 2008).

121

TENN. CODE ANN. § 48-21-108(a)(2)–(3) (2002).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

706 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

Interestingly enough, there is much room for interpretation even

amongst the state merger statutes that are very nearly identical in language.

The ―vesting‖ language has been interpreted to mean a merger constitutes a

transfer and can trigger anti-transfer provisions (PPG Industries, Inc. v.

Guardian Industries Corp.

122

). The same ―vesting‖ language has also been

interpreted to mean a merger does not constitute an impermissible transfer

such that anti-transfer provisions were not triggered (TXO Production Co.

v. M.D. Mark, Inc.

123

). Another issue arising out of interpretation of state

merger statutes based on the MBCA is the issue of the meaning of the term

―transfer‖ as it pertains to a merger. This issue was at stake in Star Cellular

Telephone Co. v. Baton Rouge CGSA, Inc., discussed in Section III B. The

Delaware Chancery Court, interpreting Georgia merger statues, stated that

because the current Georgia merger statute did not employ the term

―transfer‖ and the contract at issue did not, ―plainly and unambiguously

include mergers within the category of prohibited ‗transfer[s]‘‖ the intent of

the parties at the time of contracting would provide the context for the

effect of a merger on anti-transfer language.

124

The Official Comment to the MBCA expressly states, ―A merger is not

a conveyance, transfer, or assignment . . . . It does not give rise to a claim

that a contract with a party to the merger is no longer in effect on the

ground of nonassignability, unless the contract specifically provides that it

does not survive the merger.‖

125

What may, in part, give rise to the conflict

between the TXO and PPG lines of cases is the MBCA‘s goal of

―simplifying language describing the legal consequences of a merger.‖

126

While simplistic language is great for laymen explanations, it only provides

the foundation for litigation between legally sophisticated minds. Thus,

when a statute is called upon to fill in the gaps of an ambiguous contract,

the fact that different parties view the statutory language itself as

ambiguous and in need of further interpretation calls into question the

intelligence of simplifying the language describing the legal consequences

of a merger.

122

597 F.2d 1090, 1095–96 (6th Cir. 1979) (interpreting statutes from Ohio, Delaware, and

Texas).

123

999 S.W.2d 137, 142–43 (Tex. App.—Houston [14th Dist.] 1999, pet. denied).

124

Star Cellular Tel. Co. v. Baton Rouge CGSA, Inc., Civ. A. No. 12507, 1993 WL 294847,

*6–7 (Del. Ch. Aug. 2, 1993) (unpublished op.).

125

MODEL BUS. CORP. ACT ANN. § 11,07 official cmt. (2008).

126

MODEL BUS. CORP. ACT ANN. § 11,07 annot. (2008).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 707

B. State Statutes Based on the Model Business Corporation Act

Which Add Specific Statutory Language Regarding Transfer and

Assignment

The state merger statutes from Texas and Georgia are unique in that

they model the MBCA but add language specifically detailing the effect a

merger has on transfers and assignments. Notice that the Texas Business

Corporation Act, the Texas Business Organizations Code, and the Georgia

Code all specifically state the vesting takes place without (1) reversion or

impairment, (2) further act or deed; or (3) transfer or assignment

127

having

occurred:

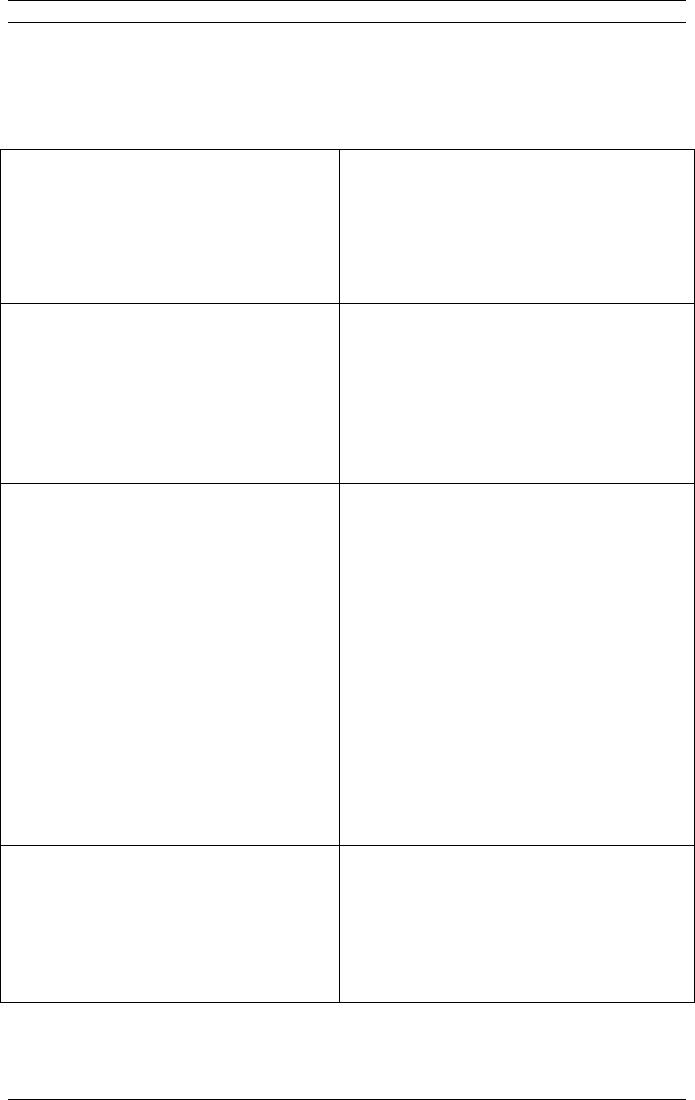

Texas (Texas Business Corporation

Act)

128

[A]ll rights, title and interest to all

real estate and other property owned

by each domestic or foreign

corporation and by each other entity

that is a party to the merger shall be

allocated to and vested in one or

more of the surviving or new

domestic or foreign corporations and

other entities as provided in the plan

of merger without reversion or

impairment, without further act or

deed, and without any transfer or

assignment having occurred . . . .

Texas (Business Organizations

Code)

129

[A]ll rights, title and interest to all

real estate and other property owned

by each organization that is a party

to the merger is allocated to and

vested, subject to any existing liens

or other encumbrances on the

property, in one or more of the

surviving or new organizations as

127

Georgia Code adds ―conveyance.‖

128

Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06 (Vernon Supp. 2008) (eff. 1955-2010. However, after

January 1, 2006, corporations formed prior to 2006 can elect to be governed by the Business

Organizations Code).

129

Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code Ann. § 10.008(a)(2) (Vernon 2007) (eff. Jan 1, 2006).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

708 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

provided by the plan of merger

without:

(A) reversion or impairment;

(B) any further act or deed; or

(C) any transfer or assignment

having occurred . . . .

Georgia

130

The title to all real estate and other

property owned by, and every

contract right possessed by, each

corporation or entity party to the

merger is vested in the surviving

corporation or entity without

reversion or impairment, without

further act or deed, and without any

conveyance, transfer, or assignment

having occurred . . . .

The 1996 Comment of the Texas Bar Committee on the 1987

amendment to Article 5.06 of the Texas Business Corporation Act states

that the amendment was made ―to make clear that while a merger vests the

rights [and] privileges . . . this is accomplished without a transfer or

assignment having occurred. Prior to the 1987 amendment of TBCA,

Article 5.06A, it was possible that a merger could have been viewed to

constitute a transfer . . . .‖

131

From this language it is clear that Texas courts

are expected to find no transfer to take place in a merger when the Texas

merger statute is used to reach a conclusion.

The ―Comment‖ to the Georgia merger statute also states, ―A merger is

not a conveyance or transfer, and does not give rise to claims of reverter or

impairment of title based on a prohibited conveyance or transfer.‖

132

While

the Georgia statute, like the Texas statutes, also dictates that a merger is not

a transfer, there appears to be some uncertainty on the definitiveness of

such language. As the Star Cellular holding (which was an interpretation

of the Georgia merger statutes) dictates, the court may face certain

130

GA. CODE ANN. § 14-2-1106(a)(2) (West Supp. 2008).

131

Tex. Bus. Corp. Act Ann. art. 5.06 (Vernon 2003) (Comment of Bar Committee 1996).

132

GA. CODE ANN. § 14-2-1106(a)(2) cmt. (West 2003).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 709

circumstances in which a material increase in risk or harm resulting from

finding the merger to not trigger the anti-assignment or anti-transfer clauses

of the contract may result in a different conclusion than intended by the

legislature.

133

The question remains as to whether a court interpreting Texas or

Georgia merger law will in fact follow the advice of the Star Cellular court

and find a reasonable middle ground in opposition to the rule that a merger

does not constitute a transfer or assignment. Thus, a Texas court might

decide to enforce the provisions in opposition to the legislative intent

behind the statutes, where holding otherwise leaves the non-breaching party

to the contract in a situation of increased risk or harm due to the court‘s

refusal to enforce the anti-assignment and anti-transfer provisions of the

contract. Under such circumstances, one finds the court making a legal

conclusion based on what is fair to the non-breaching party, a situation

which seems to call on the basic foundations of equitable relief.

C. State Statutes Which Do Not Mention “Vesting”

As the term ―vesting‖ has garnered so much judicial attention, certain

state legislatures have discontinued the use of the terms entirely. It is

important to note that while these two statutes are grouped together under

the same heading, they are in no way similar other than the fact that neither

statute makes use of any ―transfer‖ or ―vesting‖ language. Ironically, these

statutes constitute two different ends of the spectrum:

Pennsylvania

134

When a merger or consolidation

becomes effective, the existence of

each party to the plan, except the

resulting institution, shall cease as a

separate entity but shall continue in,

and the parties to the plan shall be, a

single corporation which shall be

the resulting institution and which

shall have, without further act or

deed, all the property, rights,

133

Star Cellular Tel. Co., v. Baton Rouge CGSA, Inc., Civ. A. No. 12507, 1993 WL 294847,

*6–9 (Del. Ch. Aug. 2, 1993) (unpublished op.).

134

PA. STAT. ANN. § 1606(c) (West 1995).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

710 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

powers, duties and obligations of

each party to the plan.

Puerto Rico

135

[A]ll rights and properties of the

nonsurviving corporation shall be

considered as transferred to the

surviving or new corporation

without need of further proceedings

or conveyance, and the surviving or

new corporation is bound to the

obligations and liabilities of the

merged or consolidated

corporations as if contracted

directly by such surviving or new

corporation itself.

The language utilized in the Pennsylvania merger statute is much

different than the Puerto Rico statute because it makes the interpretation of

statutory language less open to litigation based on ambiguity. The phrase

―shall continue in‖ is much more direct than the use of ―transfer‖ or

―vesting‖ is. The statute specifically details that each party to the merger

plan, except the resulting institution, ceases to exist entirely as a separate

entity. However, while the separate existence is technically gone, it

continues on in the surviving entity. There is no room for different

interpretations, the entire existence of the previous entity—all rights,

privileges, properties, debts, powers, etc—continues on within the new

entity.

Puerto Rico, on the other hand, uses much more ambiguous language.

All the rights, etc. that technically transfer from the non-surviving

corporation to the surviving corporation are merely ―considered‖

transferred.

136

They are not just transferred, there is no direction that they

―shall be‖ transferred, the court is just instructed to ―consider‖ the rights

and properties to be transferred. According to the Merriam-Webster

Dictionary, the term ―consider‖ means ―to think about carefully.‖

137

The

major synonyms of ―consider‖ are ―study,‖ ―contemplate,‖ ―weigh,‖ and

135

P.R. LAWS ANN. tit. 26, § 2947(1) (2008).

136

Id.

137

MERRIAM-WEBSTER ONLINE DICTIONARY, available at http://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/consider (last visited Dec 5, 2008).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 711

―deem.‖

138

These terms, except ―deem‖, mean to give thought to in order to

reach a reasonable conclusion.

139

Thus, the court may not be required to

hold that a merger is or is not a transfer, the court is only required to give

thought to the idea that the rights and properties transfer to the surviving

corporation and then reach a reasonable conclusion based on that

consideration. However, in the case of the synonym ―deem,‖ a court may

also interpret the statute to ―deem‖ or ―regard‖ the merger to effect a

transfer.

140

Because ―consider‖ can be interpreted in multiple fashions,

courts could hold either way, so long as the explanation is reasonable when

considering the circumstances of the merger and the language of the

contract at issue.

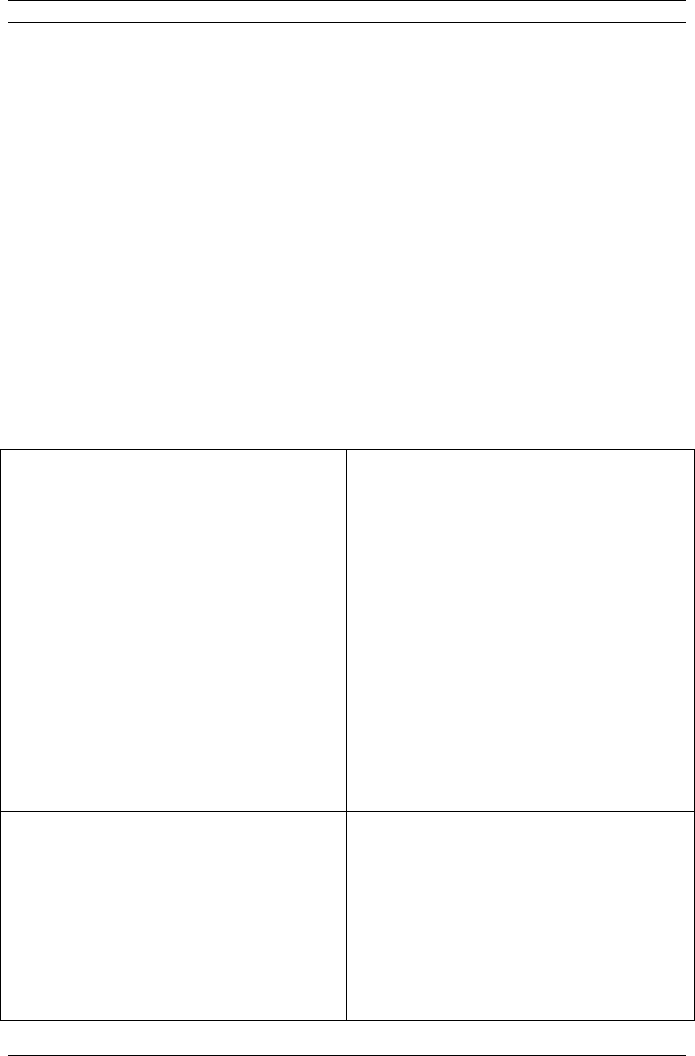

D. State Statutes Which Provide Specific Boundaries Concerning

Contractual Language

Virginia

141

When a merger becomes

effective: . . . Property owned by,

and, except to the extent that

assignment would violate a

contractual prohibition on assignment

by operation of law, every contract

right possessed by, each domestic or

foreign corporation or eligible entity

that merges into the survivor is vested

in the survivor without reversion or

impairment . . . .

The Virginia merger statute appears to be the only state statute

involving a direct reference to the ability of a contract to circumvent the

intended statutory effect of a merger governed by Virginia law. In Virginia,

a merger does not constitute a transfer unless holding so would directly

138

Id; MERRIAM-WEBSTER ONLINE DICTIONARY, available at http://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/deem (last visited Dec 5, 2008).

139

MERRIAM-WEBSTER ONLINE DICTIONARY, available at http://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/consider (last visited Dec 5, 2008).

140

MERRIAM-WEBSTER ONLINE DICTIONARY, available at http://www.merriam-

webster.com/dictionary/deem (last visited Dec 5, 2008).

141

VA. CODE ANN. § 13.1-721(3) (2006).

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

712 BAYLOR LAW REVIEW [Vol. 61:2

violate a contractual provision between the parties. Thus, the Virginia

statute appears to recognize the concept emphasized repeatedly thus far,

that parties to a contract always retain the ability to draft contracts that

circumvent the vesting effect of a merger statute.

E. What Are the Implications from the Different Language?

The main conclusion arising from this analysis is that the majority of the

statutes—those which state the rights vest in the surviving entity—leave

courts with the ability to determine whether ―transfer‖ or ―assignment‖

language in a contractual agreement can be interpreted to encompass the

merger or business transaction at issue in front of the court. Where the

drafters of the contractual agreement at issue had the opportunity to provide

that the anti-transfer clause applies to all transfers and did not, the courts

may be slow to attribute to the contracting parties the intent to prohibit

transfers where the transaction did not materially increase the risks to or

otherwise harm the parties involved.

142

In the cases reviewed for this Comment, the courts that elected to make

transfers and assignment impermissible generally did so because the effect

of the transfer or assignment created an increased risk of harm to the non-

breaching parties. Salgo provides such an example. The Salgo court chose

to deem the transfer impermissible because it forced Salgo to accept a

partner he did not consent to include in the partnership, and this would have

inequitably harmed Salgo due to the balance of voting rights and control

that could be exercised by the stranger third party.

143

On the other hand, in

Star Cellular, the court concluded that the transfer was permissible because

there was no material change in the control of the general partner or in the

operations of the partnership.

144

From looking at cases on both ends of the

spectrum, it appears fairly consistent that when an impermissible transfer

results in forcing partnership or membership in an entity, the court may be

more likely to hold that the transfer or assignment before the court was

impermissible and subject to anti-transfer or anti-assignment clauses.

142

See TXO Prod. Co. v. M.D. Mark, Inc., 999 S.W.2d 137, 141–43 (Tex. App.—Houston

[14th Dist.] 1999, pet. denied); McAleer v. Eastman Kodak Co., No. 07-02-0015-CV, 2002 WL

31686682, at *4 (Tex. App.—Amarillo 2002, pet. denied) (not designated for publication); Star

Cellular Tel. Co. v. Baton Rouge CGSA, Inc., Civ. A. No. 12507, 1993 WL 294847, at *11 (Del.

Ch. Aug. 2, 1993) (unpublished op.).

143

Nicolas M. Salgo Assocs. v. Cont‘l Ill. Props., Inc., 532 F. Supp. 279, 283 (D.D.C. 1981).

144

Star Cellular, 1993 WL 294847 at *11.

13 HAINES.EIC 8/4/2010 9:16 AM

2009] THE EFFICIENT MERGER 713

IV. OUTWITTING THE TEXAS MERGER STATUTES: IF A MERGER DOES

NOT EFFECT A ―TRANSFER‖ UNDER TEXAS LAW, DOES IT EFFECT A

―TRANSFER‖ UNDER THE UNIFORM FRAUDULENT TRANSFER ACT?

Consider a situation involving a non-traditional merger in which two

corporations merge and both survive, allocating assets and liabilities

between themselves. Texas appears to be unique in defining a ―merger‖ to

include a situation in which two entities enter the merger and the same two

entities survive the merger, with the only difference post-merger being the

allocation of liabilities and assets among the two entities.

145

Thus, two

corporations could legally ―merge‖ with the only difference post-merger

being that one corporation is allocated all the liabilities and the other

corporation is allocated all of the assets. The issue arises at this point

because under the Texas Business Organizations Code, liabilities that

entities were liable for at the time of merger remain the liabilities of those

entities and ―no other party to the merger . . . is liable for the debt or other

obligation‖ unless expressly allocated in the merger agreement.

146

This

appears to create a legal loophole because the corporation that is allocated

all of the liabilities will not have any assets to pay off creditors existing at

the time of merger. Thus, if Corporation A and Corporation B are the

surviving entities of a non-traditional merger in which Corporation A is

allocated all the debt and Corporation B is allocated all the assets

147

, would

145

Tex. Bus. Orgs. Code Ann § 1.002(55) (Vernon 2007) dictating that:

―Merger‖ means: (A) the division of a domestic entity into two or more new

domestic entities or other organizations or into a surviving domestic entity and one or

more new domestic or foreign entities or non-code organizations; or (B) the

combination of one or more domestic entities with one or more domestic entities or

non-code organizations resulting in: (i) one or more surviving domestic entities or non-

code organizations; (ii) the creation of one or more new domestic entities or non-code

organizations; or (iii) one or more surviving domestic entities or non-code

organizations and the creation of one or more new domestic entities or non-code

organizations.

146

Id. § 10.008(a)(4).

147

In Texas assets and liabilities from all parties to the merger end up where the parties

dictate in the plan of merger. See id. § 10.008(a)(2)–(3) (noting that ―When a merger takes

effect . . . (2) all rights, title, and interests to all real estate and other property owned by each

organization that is a party to the merger is allocated to . . . one or more of the surviving or new